Then & There: The Dawn of Dog

Story and photos by Richard Hooper

History generally notes that the first recognized dog show occurred at Newcastle, England, on the 28th and 29th of June in 1859. The show, however, did not spring forth fully formed from nothingness, and at least a portion of previous events that must have served as inspiration were surely dog shows of one type or another.

In the mid-1770s, John Warde (sometimes referred to as the Father of Foxhunting) held annual shows of foxhounds at Squerryes Court, his estate near Westerham in Kent. Many decades later, Warde’s shows may have influenced Thomas Parrington to push for the inclusion of foxhound classes in the Cleveland Agricultural Society’s annual fair. His efforts succeeded in August of 1859, and within a few years, over 60 hunts were represented. After several moves, the show settled in Peterborough in 1877, becoming the imminent hound show that it is today.

Other agricultural societies held shows for dogs at their fairs, such as the Agricultural Society of Durham, beginning about 1783. Less formal shows among compatriots were held at pubs and taverns on evenings when attendees were expected to bring their dogs to compare them to others and where they could be offered for sale.

In the winter of 1834, the publican Charlie Aistrop held a show of spaniels at his pub, the Elephant and Castle. The prize was a silver cream jug. Aistrop had been owner of the infamous Westminster Pit, where dog-fighting and rat-baiting contests were held. He had also been involved in bear-baiting, but was inspired to change careers after his wife was killed when feeding one of the bears.

Another publican, Jem Burns, bred bulldogs and organized bulldog shows after his retirement from pugilism in 1825. The shows were held at his establishment, the Queen’s Head, in Haymarket. In 1853, another retired pugilist, Jemmy Shaw, took over the Queen’s Head. Shaw had previously been the proprietor of the Blue Anchor, where he also held dog shows. He continued the tradition when he took over the Queen’s Head. These pub shows were, at best, semi-private gatherings of local dog fanciers. At their worst, the pubs also had rat-pits where rat-baiting took place and secretive dog fights might be held.

The Newcastle show gained its place in history for being at the forefront of dog shows that were progressing into respectability. An expanding middle-class, along with improvements in railway travel, accelerated this phenomenon. The Newcastle show was not a stand-alone event, but a side-show attached to an established poultry fair. There were 60 entries limited to pointers and setters. The organizers were John Shorthose, a brewer’s agent, and William Pape, a gunsmith. Pape, who had produced his first shotgun in 1857, was offering one of his guns to the winner of each class.

The idea for the show was originated by Richard Brailsford, who had been pushing the idea for several years. Brailsford, an employee of the Earl of Darby, also served as one of the three judges of setters and whose entry in pointers took the prize. The prize for setters was won by Mr. J. Jobbling, who, coincidentally, was one of the three judges of pointers. In November of that same year, Mr. Brailsford organized a stand-alone show in Birmingham. Again, the show was for sporting dogs only, but expanded to classes for retrievers, Clumber spaniels, and “Cockers or Other Breeds.” In pointers (large size) Mr. Brailford’s dog took a third place and his bitch took a first.

In the following year, 1860, the Birmingham show was open to sporting and other dogs and had 267 entries. Suddenly, highly respectable names such as the Viscount Curzon, Lords Bagot and Paget, the Earls of Darby and Litchfield, and Earl Spencer were among the prize winners. Also taking prizes were Mssrs. Stretch, Hanbury, Gilbert, and others without titles to their names, marking a new mingling of social strata. Mr. Brailsford, who was presented with a special medal in 1864 in recognition of his services in establishing the Birmingham show, took a prize for his retriever.

The number of shows increased, attendance grew, and breed classes proliferated. In 1863, there were two large shows in London. The first show, in March, was the six-day, first annual Grand National Exhibition. It had 1,214 entrees, with 17 classes for sporting dogs, including Russian retrievers (now an extinct breed). The non-sporting breeds had 24 classes. There were white, fawn and blue Scotch terriers, Blenheim and King Charles spaniels, black and tan terriers, white English terriers and a class known as “Other English Terriers.” There were pugs, Dalmatians and mastiffs and a class for “Large Foreign Dogs” and one for “Small Foreign Dogs.”

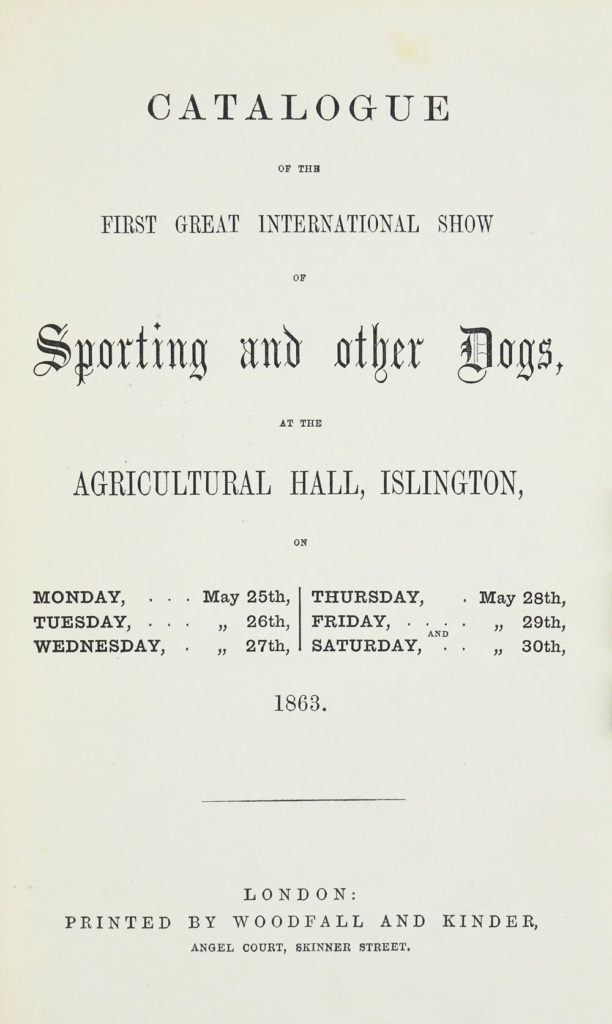

The second London show was billed as the first Great International Dog Show and was held at the Agricultural Hall, Islington. It was estimated that this show had over 2,000 entries. Again, there were two divisions: “Sporting Dogs” and “Dogs Not Used in Field Sports.” Many of the classes were the same or similar as the first London show. But in the second, there were classes for “British or Foreign Lap Dogs (Not Above Included)” which excluded the already included classes of various toy spaniels and English toy terriers. There was also a class called the “Best Monster Dog” (won by the Algerian mastiff, Samson) and a class for “Various,” where Mr. Newton’s “Diogenes” took first (we are not informed what variety of various he was).

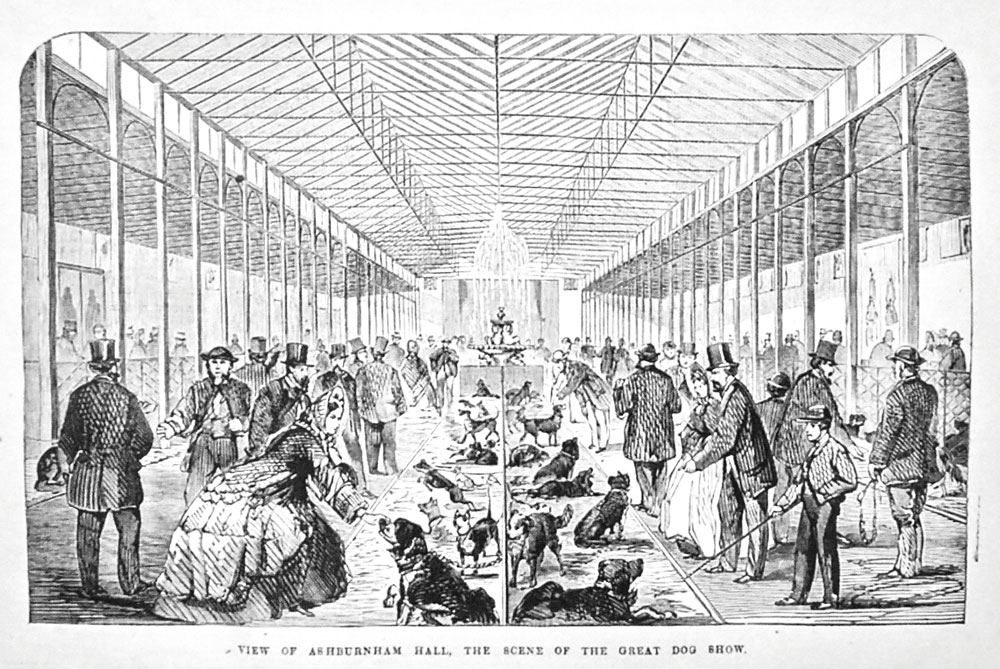

All, however, was not a smooth trajectory of successful shows, and the March London show was notable as an example of the adage that if something could go awry, it probably would. It was held at Ashburnham Hall, Cremorne in Chelsea. A major point of decoration at the show was a sparkling fountain of water, which was a delight for the attendees, but accentuated the shortage of water for the dogs. Dogs that were shipped were stressed by delays at the railway station and then began arriving at the show so fast and in such concentration that the show staff could not cope. Dogs were fastened together willy nilly and began to fight. They were then separated by wire netting until their owners arrived and began to liberate them. The dogs, now running free, began to fight again and also bite exhibitors and spectators alike.

The identities of many dogs were lost and dogs were put into wrong classes. If this was not enough chaos, winners were announced and then changed. Numerous dogs ran from the venue into the streets and disappeared. It was a bench show and a wolf from Crimea was supposed to be on exhibit at pen 1195, which attendees eagerly sought out. Their consternation must have been palpable as they discovered not a wolf, but a pair of dachshunds.

From these beginnings the great Crufts show would eventually emerge in 1891, but that is another story. ML

This article first appeared in the September 2019 issue of Middleburg Life.