A Transatlantic Rewilding Conversation Finds an Audience at the Middleburg Community Center

Written by Bill Kent | Photos by Callie Broaddus

The question came from the audience after Isabella Tree, Lady Burrell, finished her evening talk last month at the Community Center: It’s all well and good to stop mowing lawns; tear down fences; fill drainage ditches; invite deer, pigs, bears, and beavers to make themselves at home; and otherwise let nature take its course — but what are we in Hunt Country to do about invasives?

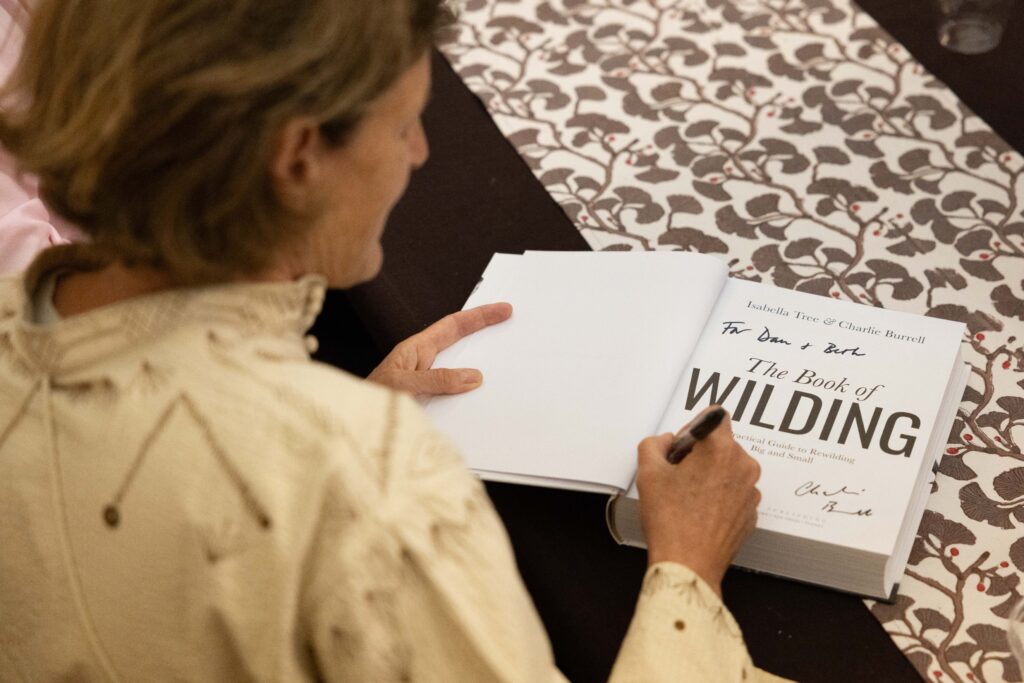

Isabella (she prefers Isabella to Lady Burrell, in the same way her husband, Sir Charlie Burrell, 10th Baronet, likes to be called Charlie, because, he quipped, “Charles is currently in use”) visited Hunt Country last month with her husband to promote their new 560-page “Book of Wilding: A Practical Guide to Rewilding Big and Small.” The visit was on all accounts successful, with Crème de la Crème selling 180 copies of the book in a matter of hours.

In answering the question, Isabella first cited what Charlie had said earlier that day. After describing a costly and ultimately futile attempt in California to end an invasive plant infestation, Charlie said that Americans may just have to “get over it!”

At the Community Center, Isabella added the hope that, “Eventually we may learn to embrace invasives.”

A shiver went through some of the 200 or so Hunt Country landowners, farmers, and members of the Piedmont Environmental Council, the Garden Conservancy, and the Oak Spring Garden Foundation which had sponsored the Burrells’ visit. Anyone who grows anything outdoors in Hunt Country knows that if invasives are permitted to take their course, some plants, bugs, and critters can destroy a garden, a tree, a vintner’s grapes, a pond, a creek, a paddock, or a forest in a few weeks.

Leaving the invasive question almost as fast as it came up, Isabella earned enthusiastic applause as she ended her talk on a positive note. Of rewilding, she said, “It brings a change in our relationship with nature. It puts us in a position of humility,” in which we work more intimately with nature, and not against it. She finished, “Perhaps the most important things we are rewilding are ourselves.”

Rewilding, as the Burrells describe it, is not new to Hunt Country. The Virginia State Arboretum in Boyce has several examples open to the public along its 2.4-mile loop nature trail.

“The 35 acres in front of the house used to be farmed,” says Jack Monsted, the trail’s assistant curator. “It’s been left alone to become one big native grass meadow.”

Other rewilding highlights along the Arboretum trail include a forest of native Virginia white oaks, red maples, and pawpaws, and other, wilder areas along the trail’s southern edge. “Rewilding — preserving some wild spaces as they are and letting native wildlife and plant species return — is one of our main priorities here,” Monsted explains.

For Laura Schultz of ReWild NOVA in Haymarket, rewilding is about caring for and rehabilitating animals that have been injured or displaced. “Most of our cases are a result of human encroachment on local habitats. People often think of cars hitting animals, but more often it’s actions like taking down trees, which have larger impacts. Clearing out dead or fallen trees this time of year is problematic for bat populations who are beginning to look for hibernation locations. [It also] destroys flying and gray squirrel nests currently filled with their young.”

Isabella, a travel writer, and Charlie, an environmental scientist, had not heard of rewilding when Charlie inherited Knepp, his family’s ancestral farm in west Sussex in 1987. The inheritance included a castle, formal garden, croquet lawn, a herd of dairy cattle, and 3,500 acres of degraded clay soil. The couple “tried to make a go of it” as farmers.

After 17 years of persistent failures on depleted clay soil, the Burrells were £1.5 million in debt. In 2001, they planted a 350-acre wild grass meadow and brought in grazing deer, hoping to create natural habitats that would eventually replenish the soil and return the landscape to what it had been before it was farmed. On the advice of Dutch biologist Franz Vera, they stopped all agriculture on their estate and reintroduced herbivores — pigs, elk, and horses — in order to “put nature back in the driver’s seat,” Isabella said at the Community Center event.

Within months wild grasses sprouted from what had been furrowed fields. After a year they noticed an increase in the number of birds, some of which, like the stork, had not been seen in southern England for centuries. On their regular morning walks, they found that birdsong became louder on the estate than the roar of jet planes flying into Gatwick Airport.

After removing fences and drainage ditches (and gaining the cooperation of neighboring farmers), the Burrells saw ponds appear, dry up, and return as the seasons changed. They reintroduced beavers on a stream running through their land, which built dams and created habitats for freshwater fish.

“With some difficulty,” Isabella related, she and her husband followed Vera’s advice not to feed, assist, or provide veterinary care to the farm’s new inhabitants. The animals adapted to the landscape, finding their own food and shelter in the brutal winter. Instead of using carnivores to limit the herds, the Burrells “assumed the role of apex predators,” deriving a limited source of high-quality beef, pork, and venison.

Perhaps spurred by the Burrells’ success, rewilding became so popular in the United Kingdom that the 2022 best-of-show winner at the prestigious Royal Horticultural Society Chelsea Flower Show was a rewilded garden, with its own beaver dam and stream.

At the Community Center Isabella shared that Knepp is now debt free, generating about £1 million a year in revenue from agritourists who want to see what has become the world’s most celebrated rewilding showcase. Visitors can tour the grounds in safari-style vehicles, take short walking tours, hike, and camp. They can assist in on-going ecological studies, spend the night in a treehouse or “glamping” accommodations, and dine in a restaurant that serves meals from ingredients harvested on the farm.

The once-depleted soil is now so rich that a recent survey determined Knepp was absorbing as much carbon as a mature forest. Rewilding, Isabella told the Community Center audience, may be the single best way to reduce greenhouse gasses and reverse the catastrophic effects of climate change.

Back in 2018, Isabella wrote a book about the farm’s transformation, incorporating anecdotal and scientific evidence for rewilding’s success. “Wilding: the Return of Nature to a British Farm” became an international bestseller, popularizing what is now a movement that claims, at its heart, that nature can fix the ecological damage wrought by human beings, if human beings would only let it. Her current book, written with Charlie, is a guide for those who want to give rewilding a try.

Some in Hunt Country have already done so.

According to Aldie-based landscape architect and garden designer Fritz Reuter, “It would be difficult to find any large-scale Hunt Country landscaping project in the last 10 years that hasn’t incorporated some kind of rewilding. The key is management. Neglect is not rewilding. You can’t turn your back on nature and expect everything to work out. If you look closely at what the Burrells have done, you see that they didn’t either.”

He calls the Burrells “kindred spirits. They have shown that what we have been doing here has merit, not just locally, but on a global scale.”

“If you put a plant that’s native to our area in a pot on a balcony,” he continues, “a pollinator will find it. If you leave the seed heads on after it flowers, a bird will eat those and connect you to the wilder natural world around you. Working with nature, rather than just letting things go, is a great way to find joy.”

Margrete and Mike Stevens wanted to do precisely that with invasive shrubs and trees at Bonny Brook Farm in Catlett. “We decided to begin this work a couple of years ago,” Margrete says, “because our tree lines were suffering from being choked and crowded out. … [W]e have established a wildflower meadow and planted, with PEC’s assistance, some 150 native trees along Cedar Run, which traverses our farm. We have also set aside an area of our wetlands to enable us to observe what the seed bank might produce; and we have some 30 acres of woods that are left unencumbered.”

Results have been slow, but worth the wait. Margrete says there has been “an increased presence of native wildflowers, from the early spring until well into fall. Our ‘liberated’ trees look much healthier.”

Bert Harris, executive director of Warrenton’s Clifton Institute, has recommended the Burrells’ rewilding books to Hunt Country landowners. The books, he says, have “many useful points that can get people motivated to do something important ecologically with their land. It’s one of many ways to understand that you really can work with nature to make things better for [yourself] and [your] neighbors.”

Part of the Institute’s mission is to offer Hunt Country landowners what Harris calls “targeted” ways to cope with invasives. “It’s not as simple as just getting over it. We have a lot of invasives in Virginia and there will never be enough time and money to get rid of them all. But we can prioritize which species we can get rid of realistically, clear out a few more and maybe learn to live with others.”

Pete Smith called the Clifton Institute three years ago for advice in rewilding his Berryville farm. He says he’s pleased with the results. “Since we’ve pulled out the autumn olive, and put in some native plants, it looks so much better. We have about 25 species of native grasses and plants now. We’ve seen more birds, box turtles, and deer. Marsha and I have the greatest respect for the Burrells. They’ve gotten us to think about what we can do with our land to keep this region strong.”

Toward the end of Isabella’s question-and-answer segment, Pat Cassidy stood up and announced that six years ago he tried rewilding most of the 110 acres on his farm. He cited Isabella’s observation that the first thing most rewilders find after a season or two of letting nature take over is an increased presence of birds.

“The first thing we noticed was the return of wild turkeys,” he said. “Then the ticks disappeared.”

Lady Tree was delighted. “Ticks used to be such a problem for us, too. Now we haven’t seen one at Knepp for 10 years!” ML

Published in the November 2023 issue of Middleburg Life.