Aldie: A Gateway into Western Loudoun

By Heidi Baumstark

Aldie. It’s the first historic village traveling west from Gilbert’s Corner. It’s basically a gateway into western Loudoun, a welcome relief from the hustle and bustle of northern Virginia.

Upon entering the village on John Mosby Highway (Route 50), visitors behold an old white church, cross over a stone-arched bridge, notice the huge brick mill mingled with a multiple of other historic structures, and can’t help but wonder about the origins of this tiny hamlet located in a gap between the Catoctin and Bull Run Mountains through which the Little River flows.

Recently, members of the Aldie Heritage Association (AHA) embarked on an effort to save parts of a 19 th-century brick wall that was built by 1809 and removed sections that were leaning and crumbling due to erosion and age.

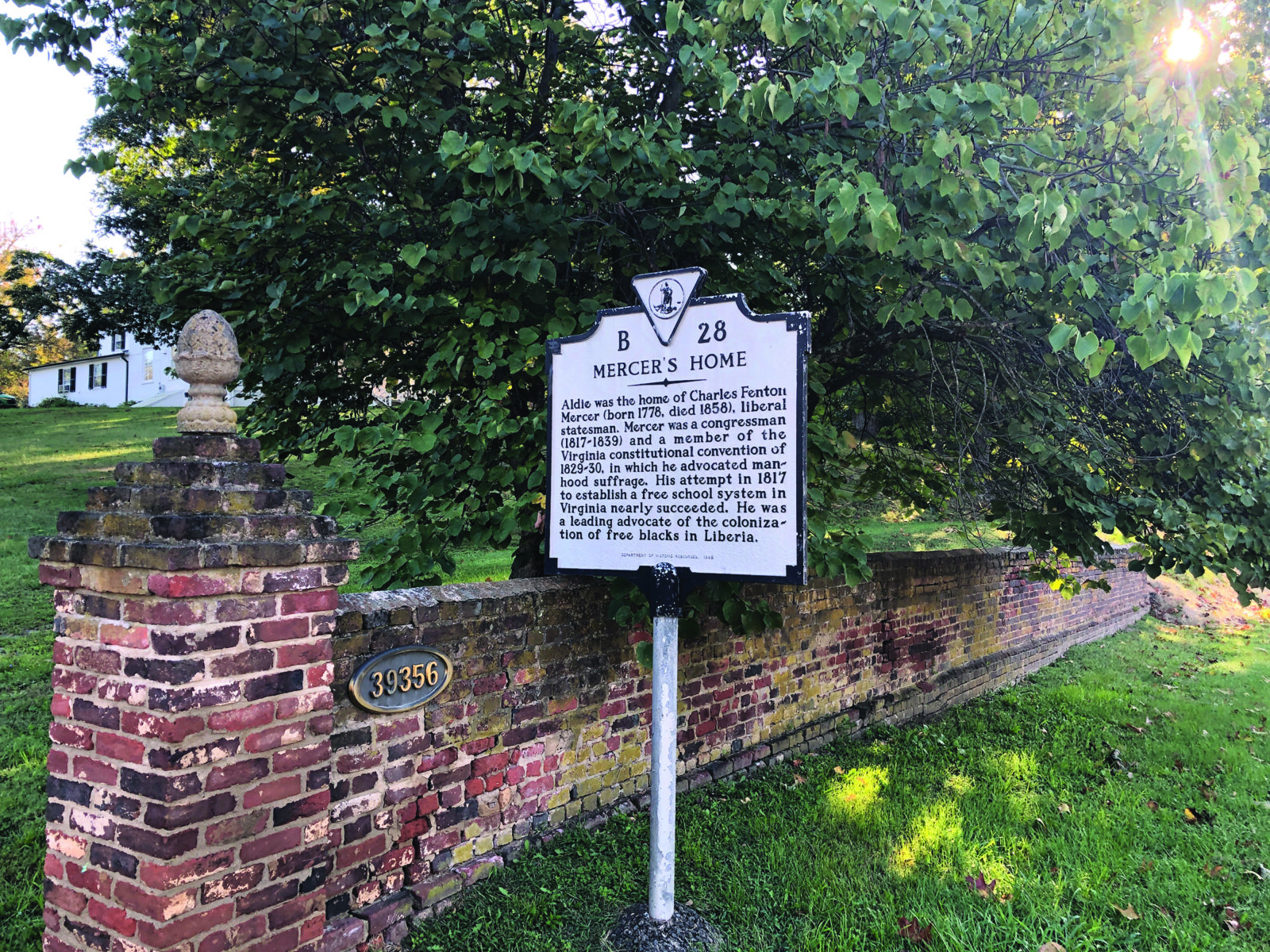

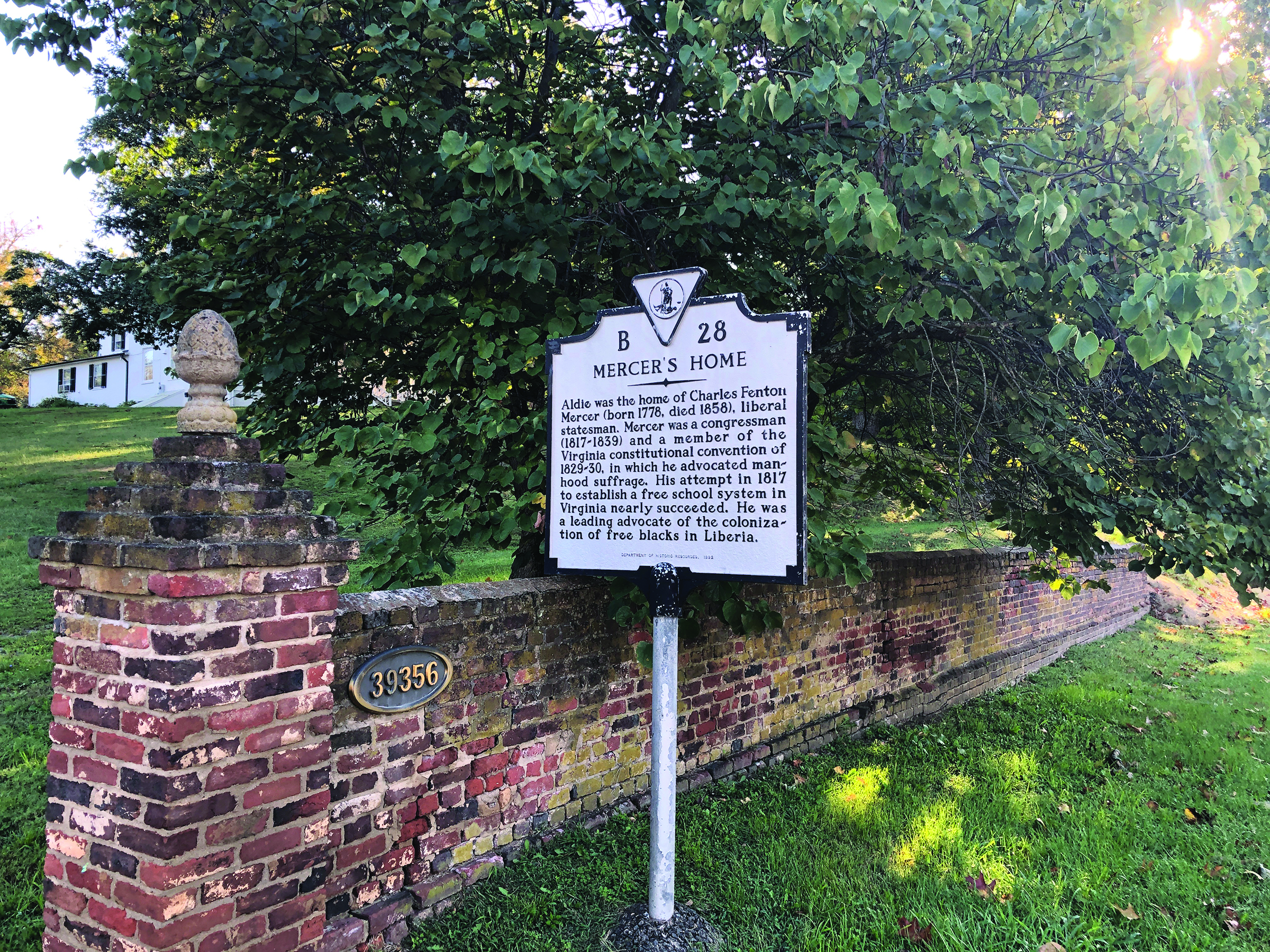

(Above: Volunteers from Aldie Heritage Association (AHA) and the Aldie Ruritan Club carefully removed bricks from an historic brick wall this summer in front of the 19th-century home of Charles F. Mercer who founded Aldie in 1810 and built Aldie Mill and other structures in the village.)

That’s because AHA’s mission is to promote, protect, and preserve the village of Aldie that grew up in the early 1800s centered around the iconic Aldie Mill, built 1807-1809. The mill’s construction was financed by Charles Fenton Mercer (1778-1858) who became a respected U.S. Congressman, was a member of the Virginia General Assembly, and a served as a member of the Virginia Constitution Convention, and William Cooke. Mercer built his house directly across the turnpike (today’s Route 50) from the mill and is credited as Aldie’s founding father, establishing the town in 1810. And in front of his house stands portions of the old brick wall.

Originally, the wall began near “Narrowgate,” the circa 1811-built brick home of Aldie’s first postmaster, and now a private residence, and it went to Tail Race Road near the entrance of the village. But it has seen better days since most of the wall closer to Tail Race has fallen with bricks piled to the ground. Other parts of the wall were leaning posing a hazard of falling altogether.

That’s when Aldie resident, Neil Conley, decided to research the wall to see what portions could be salvaged. Conley said, “I began my research to have the wall cleaned up. Once I discovered its historical significance, I tried to save what was salvageable.”

(Above: Wheelbarrow of bricks from the old Aldie wall built in the early 1800s.)

AHA’s vice president, Laura Tekrony, of Aldie, said, “We wanted to preserve what we could. So, we hired a stone mason with experience in historic preservation who advised that a 65-foot portion of the original 900-foot wall could be saved.” AHA tried to keep most of the wall, which in its entirety, was built using lime cement. Later, in the 1960s, Portland cement was used to patch a portion of the wall.

Conley’s research in 2018 led to his discovery of a March 29, 1809 plat and survey of the Aldie Mill lot filed by Mercer and Cooke. The significant wording on this plat—describing it as a “brick fence” with unique survey points and lines—indicates belief that Mercer had the wall built by 1809.

Other evidence that Mercer had the wall built, points to the fact that he was the only person who owned all the properties on which the wall sits. “Based on historical photos,” Conley concluded, “the wall began at least at the western edge of Tail Race Road, went westward along the front of Mercer’s house, extended near the current post office, and met up with the brick wall in front of Narrowgate. It served as an aesthetic feature with a functional purpose separating his home from turnpike traffic.” Tekrony said, “Since Neil did so much work researching the wall, I encouraged him to join AHA; he’s now on our board.”

In July and August, with the help of volunteers from AHA and the Aldie Ruritans, they formed a crew to carefully remove the crumbling portions of the wall. She said, “We stored about three pallets of historic bricks and we’re keeping them for potential future uses. We didn’t want to lose those bricks.” AHA is willing to invest in hiring a stone mason to fix/shore up the remaining 65-foot wall to protect it from further age deterioration. They also hope to get it placed on the historic national register through the Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Tekrony said, “If the wall has historic designation, it can be better protected.” Conley said,

“What started as a desire to clean up the village turned out to become this research project and discovering the history of this wall.”

Neil Conley

An authority about the area’s heritage is respected historian and professional mapmaker, Eugene M. Scheel, of Waterford. In his book, “Loudoun Discovered: Communities, Corners & Crossroads, Volume Three,” he notes that the village was part of a 1,449-acre grant from Thomas, sixth Lord Fairfax, to Thomas Owsley in 1740. The largest tributary of Goose Creek, called Little River, runs through the mountain gap, and this flowing water was needed for milling operations. Prior to Charles F. Mercer establishing the village in 1810—his father, James Mercer and James’ brother, George—operated a small tub mill known as Mercer’s Mill from about 1764 at or near the location of the current mill.

(Above: A historical marker in front of the 19-century home of Charles F. Mercer, Aldie’s founder, who was a noted U.S. Congressman, member of the Virginia General Assembly, and member of the Virginia Constitution Convention of 1829-1830. The brick wall in front of his house dates to the early 1800s. Photo by Heidi Baumstark.)

Charles F. Mercer settled in Leesburg in 1804 where he practiced law. In 1807, he signed an agreement with contractor William Cooke “who was to build a large wheat and corn mill, sawmill, store, miller’s house, dwelling house, and combined blacksmith, wheelwright, and cooper (barrel-maker) shop,” according to Scheel’s book.

In 1810, Mercer was elected to the Virginia General Assembly and had established his complex of buildings as a town laid out on 30 acres. He named the town Aldie after his family’s ancestral home, Aldie Castle in Perthshire, Scotland. Mercer was also appointed a lieutenant colonel of a Virginia regiment in the War of 1812.

By 1813, the Ashby’s Gap Turnpike was completed from Aldie to Middleburg, and by 1827, the stone-arch bridge over the waters of Little River, was built. In 1817, Mercer moved to Leesburg and was elected as a U.S. Congressman serving 11 terms until 1839. He was a member of the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1829-1830.

Conley’s research also revealed that Mercer was the first president of the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal, and while in Congress, served as Chairman of the Committee on Roads and Canals from 1831-1839. He was known as a champion of free public education, suppression of the slave trade, and supported the colonization in Africa for freed slaves. In 1835, Mercer sold the mill to John Moore who was one of the few Union sympathizers in the area and who did not vote for secession. In fact, Federal troops did not

burn Aldie Mill in November 1864 because of Moore’s Union affiliation. For six generations, Moore’s descendants operated the mill until 1971.

(Above: A March 29, 1809 plat and survey of the Aldie Mill lot filed by Charles F. Mercer and William Cooke.)

With his commercial and public service work out of the way, in 1845, Mercer wrote “An Exposition of the Weakness and Inefficiency of the Government of the United States.” The following decade in 1858, Mercer died, just three years before the 1861 start of the Civil War that would see cavalry troops right through the town he established. As part of the Gettysburg Campaign, in June 1863, cavalry actions along the Ashby’s Gap Turnpike (Route 50) took place.

General Robert E. Lee was moving his Confederate army up the Shenandoah Valley in June 1863 toward the west of the Blue Ridge Mountains, planning to cross the Potomac River in Maryland and push further north into Pennsylvania. Aldie was the Union’s staging ground with the Battle of Aldie breaking out on June 17, 1863. Just up the road, the Battle of Middleburg broke out June 17 to June 19; a bit further west the Battle of Upperville was fought on June 21.

These three battles resulted in inconclusive outcomes and were the prelude to the July 1-3, 1863 Battle of Gettysburg that was a Union victory and is often described as the war’s turning point and bloodiest battle of the Civil War that ended in 1865. But back to the wall, Scheel believes, “It’s a piece of Aldie’s history that still stands as a reminder of the village established over 200 years ago.” Tekrony said, “Neil was so passionate about this wall and has done so much research on it.”

To show its historical significance, maybe a plaque on the wall with a description that it was restored by AHA could be added. “Hopefully we’ll save a little history in the process,” Conley said. “It’s been about two years in the making,” Tekrony said, “and after several people stepped in, including officials in Loudoun County, the Commonwealth Transportation Board, and VDOT, we’ve taken careful steps in saving portions of the wall.

The village has such great history and needed a little love. After all, we’re a preservation group and we wanted to preserve this gateway into western Loudoun.” ML

This article first appeared in the November 2019 issue of Middleburg Life.