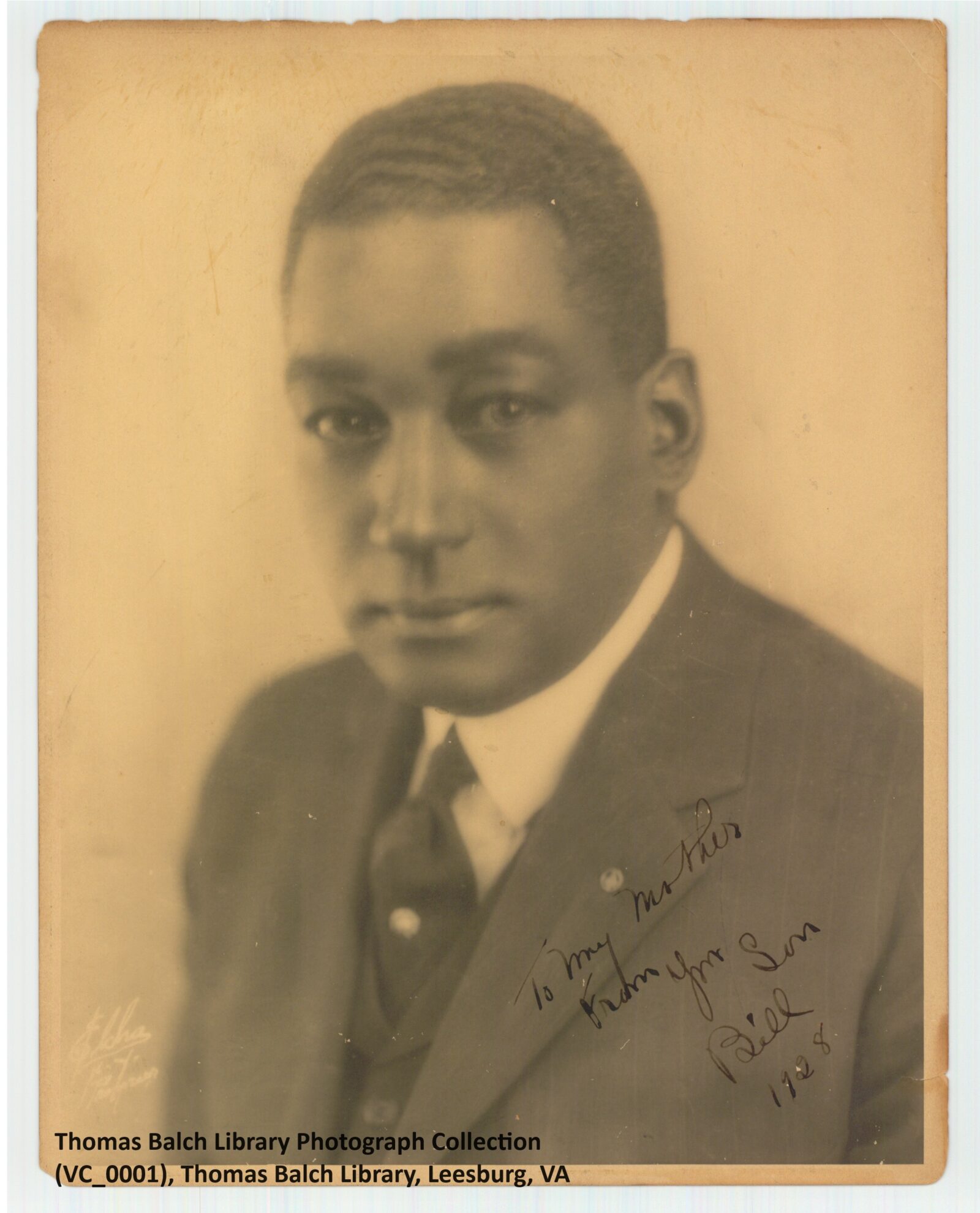

Billy Pierce: Local Legend and Renaissance Man

Written by Diane Helentjaris

Renaissance man. What else would you call a dancer who carved out a career in New York City, the toughest of all stages, or a businessman who ran “the largest dance studio in the world,” wrote for the leading African American newspapers of the day, and fought in one of World War I’s fiercest battles?

William Joseph Pierce, a legendary Hunt Country local, did exactly that. An only child, he was born in Purcellville, Virginia, on June 14, 1890. His mother, Nellie, had been enslaved in Loudoun County. Of his father, Dennis, in an Evening Star newspaper article published July 28, 1929, Pierce shared:

My father’s name was Dennis Pierce. He trained horses, was owned by Dr. Keen of Unison, in Upper Loudoun, and was the body servant of Col. John Mosby. Until Dad’s death, some years ago, he raised and lowered the flag daily at Ball’s Bluff Soldiers’ Burying Ground, near Leesburg. The only person I ever worked for in Loudoun was Mr. Rodney Purcell… I carried the little bag of mail to and from the depot and did chores around his combination store and post office.

Dennis Pierce made time for his community, an example his son would follow. He was a founding director of the Loudoun County Emancipation Association. The mutual aid organization purchased 10 acres in Purcellville in 1910 which became a center for African American community life. Today, a Virginia historical marker on 20th Street commemorates the Loudoun County Emancipation Association Grounds. A few blocks away still stands the white clapboard house where Billy Pierce grew up.

Both his parents were literate, and they made certain Billy was too. As a child he attended Colored School B, two miles down the road in Lincoln. The two-room schoolhouse was built in 1865 on land donated by Quakers. Now a private residence, it still retains its original footprint with a stone first floor, clapboard second floor, metal roof, and deep-set windows.

In the same interview in 1929, Pierce recalled:

It was in this little country school at Lincoln, [a] Quaker settlement, that I went to school. I think the greatest factor in shaping my future as to right thinking was received from a fine little Quaker lady, Miss Cornelia Janney, who used to come down to the ‘Hollow,’ as it was called, and read and lecture to us every Friday afternoon. Those talks and what they stood for I have carried all through life.

As he grew older, Pierce went to Storer College, a historically Black college, 18 miles north in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. Storer began as a one-room elementary school for freedmen. To form the campus, the federal government donated land and four buildings which originally served as housing for the staff and workers at the destroyed armory. Over time, Storer expanded into a school dedicated to training elementary school teachers and a preparatory school for students seeking higher education. College status was granted after Pierce’s time there. Storer College closed in 1955 with the passage of the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, Supreme Court ruling, and the buildings and campus returned to the federal government. Its campus and three of its buildings are now part of the Harpers Ferry National Park.

However, Billy Pierce enrolled in Storer to prepare for college, not a teaching career. After Storer, he went on to study at Howard University, the historically Black college in Washington, D.C. He did not graduate. He then worked as a journalist, writing about the arts for several African American newspapers, first in Washington, D.C. and then in Illinois for The Chicago Defender, the leading African American newspaper at the time.

In June of 1918, Pierce was drafted into the then-segregated U.S. Army infantry. The 1929 Evening Star interview reported he reached the rank of lieutenant in the 369th Infantry, known as the Harlem Hellfighters, and fought at Argonne, France. The Meuse-Argonne Offensive resulted in overwhelming loss of life and injuries. Over 1 million American soldiers fought to halt the Germans. Of these, 26,000 died and over 120,000 were injured.

After the war, Pierce returned to Washington, D.C., and journalism, but was called away by his dream of a career in the arts. He tried out a variety of gigs — he danced, played the slide trombone, took tickets at the door for a minstrel show, and played the banjo for “Dr. Diamond Dick’s Kickapoo Indian Medicine Show.” By the 1920s, he was working on Black vaudeville for the Theater Owners’ Booking Association. TOBA was notorious for its poor business practices and earned the nickname “Tough on Black Actors.”

Stranded when the minstrel show came to a screeching halt in Union Hill, New Jersey, a penniless Pierce headed for New York and never left. It was 1923 — a dynamic time, the zenith of the cultural and intellectual flowering known as the Harlem Renaissance. Pierce began his career as a choreographer and dance instructor by renting a small upstairs room as a dance studio in the Navex Building at 225 West 46th Street for $35 a month. He eked out a living operating the elevator in the building. Until the 1960s, elevators were not simple push button affairs, but required a live person to control their speed, open doors, and make sure the floor of the elevator and the building were even when they stopped. Pierce also bought a desk with a bit of cash down and a monthly payment of $4. The first year he did not always make the rent, nor the payment on his desk. More than once, he was padlocked out of the studio and his desk was seized by sheriffs until he came up with the money that was due.

By 1929, Pierce had turned things around. He had 600 registered students, rented five rooms on the first floor in the Navex Building for $6,000 a year, oversaw 11 employees, and held 27 classes. He claimed to have the largest dance studio in the world.

Those were the days of flappers, Prohibition, and the Jazz Age. Most of his students were white, a combination of performers who needed to master the jazz-influenced steps wildly popular at the time and society people who wanted to shine at parties. He worked with some of the most famous and accomplished performers of the age — people like Fred Astaire, Fred’s sister Adele, Ethel Barrymore, and Buddy Ebsen, who later starred as Jed of “The Beverly Hillbillies.”

Pierce summed up his dance philosophy: “You’ve got to learn to take life easy if you want to learn to dance. You can dance if you can walk, but you’ve got to walk like you’re all filled up with the happiness of living and like you ain’t going nowhere and in no hurry to get there.”

He choreographed Broadway shows and helped struggling shows fix their choreography troubles. Typically, his work went unacknowledged. An exception occurred in 1930: He and his assistant Buddy Bradley traveled to London to stage the dances for the British musical “Ever Green” and were credited in the program and materials.

Pierce dedicated himself to constant innovation and to the development of unique routines for each of his customers. To do this, he said, “I travel all over the South in quest of new material for Broadway, visiting all the rural communities and attending small-town dances. The ideas that I get are new to Broadway, but old to the Negro.”

Billy worked with his instructors to transform this inspiration into novel routines and dance steps. The Billy Pierce Studio was known for such dances as the Eccentric Buck, the Flapper Stomp, the Stair Dance, and the Syncopated Buck. Pierce is credited with inventing the Black Bottom dance. The Black Bottom, like the earlier Charleston, became popular and spread to mainstream America. Scholars believe the dance was rooted in turn-of-the-century New Orleans, but it was Pierce’s version which gained prominence and his name which was published on 1920s sheet music as the originator.

Despite his success, he never severed his small-town roots. Once a month he traveled back to Loudoun to visit his widowed mother. His studio’s décor, with jazzy red and green walls, included “a picture in oil on canvas of Col. Dick Delaney’s old home in Welbourne. Some of the studio frescoes show wheat fields at harvest time, corn shucking, and activities in Loudoun home life,” according to the July 28, 1929, Evening Star article by Josephine Tighe. He served on the board of the Loudoun County Emancipation Association and was active in the Elks. He also advocated for the Scottsboro Boys in 1931, a group of African American men wrongfully accused of rape and sentenced to death in Alabama.

In 1927 he married Nona Stovall, and would go on to have two children with her. Over the years, Pierce grew heavy and suffered from diabetes. He no longer danced but patted and tapped out the beats to his dances. In 1933, he developed mastoiditis, a skull infection usually caused by an ear infection. Antibiotics would not be available to the public for another decade. Pierce died at age 42.

Theatrical and society people, including Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, crowded Pierce’s funeral at the Metropolitan Baptist Church in Harlem. New York Age newspaper recounted that the minister delivered “an old ‘down home sermon’ … and told everybody to forget about Broadway and think about the church.” Papers as far away as Omaha eulogized Pierce as “Harlem’s ambassador to Broadway.” From Manhattan, his body was sent to Washington, D.C., for a second funeral. William Joseph Pierce was buried on Easter Sunday in Lincoln at Mount Olive Baptist Church’s graveyard. He shares a tombstone with his parents and maternal grandmother. His old Quaker elementary school is a short walk away, down a leafy road and across a small creek.

Loudoun remembers Billy Pierce, too. He was included in the 2002 book “Essence of a People II” by Y. Kendra Hamilton. The 2004 report “Loudoun County American Historic Architectural Resources Survey” suggested Pierce’s childhood home be evaluated for potential listings in the Virginia Landmarks and National Register of Historic Places. The report was sponsored by the Loudoun County Board of Supervisors and the Black History Committee of the Friends of the Thomas Balch Library. In 2007, his daughter-in-law Lemoine Pierce wrote the monograph “Billy Pierce,” which was published by the Black History Committee of the Friends of the Thomas Balch Library. In 2022, a community group suggested the renaming of Business Route 7 in Purcellville to the Billy Pierce Memorial Highway. Though the formal name will be “Leesburg Pike,” this suggestion was accepted. Pierce was also recognized for his part in the Harlem Renaissance in Louis Henry Gates Jr.’s book “Harlem Renaissance Lives.”

Pierce’s personal legacy lives on. His great-granddaughter is a choreographer, active in the Harlem arts scene. Lemoine Pierce noted in the introduction to her monograph:

When my granddaughter was born in 1993, we all watched in amazement when as she learned to walk steadily, she also began spontaneously to dance and choreograph her own routines! It was clear to us right away that she had inherited her great-grandfather’s talent for dance. I knew then that the time had come to learn more about Billy Pierce, about whom we all really knew so little.

To learn more, visit the Thomas Balch Library or Harpers Ferry National Historical Park. ML

Thomas Balch Library

208 West Market Street,

Leesburg, Virginia 20176

(703) 737-7195

leesburgva.gov/departments/thomas-balch-library

Harpers Ferry National Historical Park Visitor Center

171 Shoreline Drive

Harpers Ferry, West Virginia 25425

(304) 535-6029

nps.gov/hafe/index.htm

Published in the February 2024 issue of Middleburg Life.