Chernobyl: A Surreal Experience

By Laticia Headings

I’ll be honest, I had trepidation. To visit a place like Chernobyl is too rare an opportunity to pass up given my wanderlust impulses, however, all those radiation stories gave me pause. A week-long work trip to Kyiv, Ukraine, a place I’d never been to before, seemed like a sufficient enough adventure.

(Above Left to Right: Outside movie theater & Kindergarten)

My company, Latitude Media, was producing a series of messaging videos for the U.S. Department of Defense, and Ukraine was our first stop. After wrapping, my colleague and friend, Kristi Pelzel, and I decided to stay a couple of days and agreed that Chernobyl would, no doubt, be a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

It was just that. And much more. Following that tragic day on April 26, 1986, Chernobyl became synonymous with the world’s worst nuclear disaster in history, and there was something eerily fantastic about seeing that up close and in-person.

(Above: Amusement park)

Chernobyl isn’t a place you can conceptualize in your head, even when you’re there. It’s the most surreal place I’ve ever visited. Your brain registers that what you’re seeing is a ghost town ruined by war when there’s never actually been a bomb dropped there at all. Everything that once thrived in this place has succumbed to radiation and time. In 1986, there was a permanent evacuation. Dilapidated buildings riddled with broken windows and vandalized walls tell the story of decades of neglect. Schools, apartment buildings, stores and public spaces all stand the test of time with no caretakers.

(Top Left to Right: A Hotel & Semyon the Fox. Bottom: A room inside a middle school)

By law, no public or private tour group can enter the area without permission from the Ukrainian government. With a licensed tour guide, 70,000 people a year are granted access to the Exclusion Zone for roughly $100 per person. This is the 30-kilometer (19-mile) radius surrounding the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant and epicenter of the reactor meltdown, and Pripyat, the neighboring city where plant workers and their families

once lived.

Restrictions include wearing long sleeves, pants and closed-toe shoes (despite temperatures in the 80s), keeping car windows closed, and stopping at military checkpoints. I was also told not to crouch too low to the ground when taking photos because most of the radiation lives in the soil.

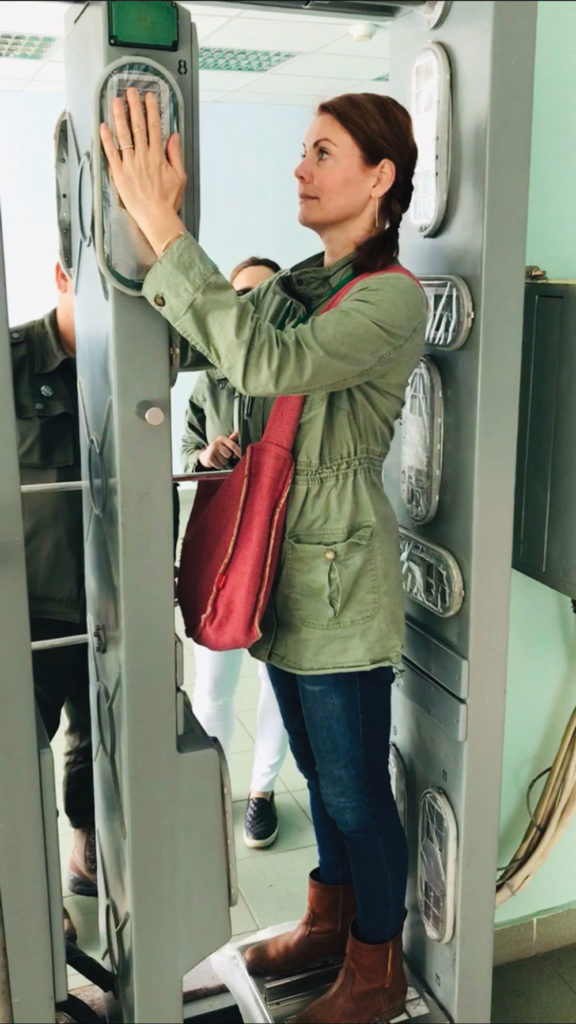

When entering the first military guard post at the edge of the Exclusion Zone, you are given a small dosimeter to wear around your neck to monitor radiation. The closer you get to the meltdown site, the more precautions are mandated. At certain points entering and exiting, you have to stand on metal detector-like turnstiles to measure the level of radioactive dust exposure. Luckily, we passed each time, meaning the radiation was within a normal range.

(Above: Chernobyl reactor site with dome)

Having a car allowed us to travel within the Exclusion Zone without restriction or being tied to a tour group timeline. Eugene “Euge” Risunkov, our witty in-country film coordinator (or “fixer”), drove Kristi and me to Chernobyl and secured us a private tour guide.

Vladimir Verbitskiy, a 30-year military veteran in his late 50s, has been working in and around Chernobyl for three decades, most recently giving tours. Born and raised in neighboring Belarus located across the Pripyat River, Vladimir vividly recounted the day the reactor melted down, his family’s evacuation, and the disastrous aftermath he endured for years. With Vladimir’s superior historical knowledge of the region and Euge’s swift translation of Ukrainian to English, Kristi and I listened to story after story in jaw-dropping awe.

(Above: Dosimeter Chernobyl with dome in background)

In addition to the individual radiation trackers we wore, Vladimir had an “official” dosimeter that measured levels as we entered different areas. At the first checkpoint, the levels measured 0.05 Sv, about the same amount of radiation you get from a dental X-ray. By the time we were inside Pripyat, it went up to 0.42, roughly the same as a mammogram X-ray.

As we drove past the reactor meltdown site, now encased by a giant dome-shaped shield, the dosimeter started beeping like an agitated guard dog barking at intruders. It peaked at 1.85, a level of exposure you don’t want for a prolonged period of time. It’s an unsettling feeling, only rivaled by the excitement of knowing you are squarely in front of the Chernobyl reactor meltdown site.

There are several forests on the first leg of the drive. Vladimir told us that no trees may be touched or removed because they are considered radioactive trash. The same goes for the buildings, which is another reason for the horrible state of disrepair. The roads in and out are scarred with bumps and holes, but there are no construction workers patching them, as that would stir up radioactivity.

(Above: Lunch)

Pripyat is an abandoned city of sizeable proportions that echoes a lost era. You can almost see the lifeforce it once had behind the vacancy that now permeates every boulevard. Traipsing through the streets, with every building and public space entangled by trees, you can still see remnants of the Soviet era everywhere.

One of the more freakish things we witnessed, and there were many, was the abandoned Pripyat amusement park that was set to open one week after the explosion. A huge yellow Ferris wheel sits high above the park, flanked by rusty bumper cars and other decrepit rides where laughing children never played.

My favorite part of the day was seeing the Chernobyl fox. Just like Middleburg, Chernobyl has foxes in residence, including an iconic one named Semyon, whose face is put on T-shirts and sold at the souvenir shop. Upon entering Pripyat, we encountered a tour bus stopped in the middle of the road surrounded by lucky tourists who spotted Semyon. When I got out of the car to take a photo, the fox turned and came straight my way as if he knew I wanted to bring him back to the ‘burg! It was truly an epic moment and luckily captured on video. (For the record, animals in Chernobyl must stay in Chernobyl for obvious reasons.)

(Above: Gas mask inside the middle school)

Semyon is in good company. Over 60 different species of wildlife inhabit the area and even thrive there. We also saw many stray dogs running around, most of them tagged and tracked by scientists. Surprisingly healthy looking, these 300 or so canines are well fed by the military personnel and soft-hearted tourists who give them leftovers from the one public cafeteria in the area.

Open from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m., Canteen 19 is the only place to get food. It supports Chernobyl’s onsite workers and is open to tourists who get a complimentary meal as part of their tour. It’s only a couple of miles from the reactor site, but all the food is brought in from outside the Exclusion Zone and is entirely safe to eat. For lunch, we dined on delicious quintessential Ukrainian fare, including borscht, chicken plov, vegetable salad, homemade bread and cream-filled crepes.

Our last stop of the day was Middle School Number Three, where hundreds of gas masks still lay strewn on the floor. Just behind the school another building with blown-out windows houses an Olympic-size swimming pool. Walking through these buildings ravaged by neglect and vandalism, we were continually navigating gaping holes in the floor, side-stepping broken glass, and climbing up and down hazardous staircases.

No authorities are looking over your shoulder or monitoring your whereabouts inside the Exclusion Zone so, in that sense, you are completely free to roam. Throughout the day, I couldn’t help but think two things: 1) This was the biggest “at your own risk” adventure I’d ever taken, and 2) This would clearly NEVER be allowed in the US of A.

(Above: Radiation detector turnstiles)

HBO’s miniseries, Chernobyl, has brought renewed interest to this area that has been a subject of concern and fascination for years. Before my trip, I intentionally watched only one episode because I wanted my observations to be unfiltered. I still haven’t finished watching the rest of the series, mostly because I want to keep this unbelievable experience all my own for a little while longer.

I have seen a lot of places. Traveled to five continents and countless countries. Visited monuments and sacred places. Traversed big cities and small towns. Trekked up mountains and hiked to remote areas. Without doubt, Chernobyl is the most extraordinary place I’ve ever had the privilege to see. Just like the effects of radiation, this trip will stay with me for a long time. ML

About: Laticia Headings is a producer, writer and camerawoman with 22 years of television, documentary film and multi-media experience. She discovered Middleburg when attending the first Annual Middleburg Film Festival in 2013 and now lives here with her husband, Christian, and dog, Sadie.