Environmental Outreach with The Clifton Institute

Written by Heidi Baumstark | Photos by Callie Broaddus

A few miles outside of downtown Warrenton is The Clifton Institute, a nonprofit in Fauquier County on a mission to inspire a deeper understanding and appreciation of nature, to study the ecology of our region through targeted research, and to restore and conserve native biodiversity. Its 900-acre property provides a stunning backdrop for a plethora of year-round programs and is protected through a Virginia Outdoors Foundation conservation easement, forever preserving the Piedmont’s wildlife.

The Institute’s field station has a mosaic of habitats, including forests, grasslands, shrublands, wetlands, streams, ponds, and vernal pools, each of which is home to a different community of plants and animals. Many may recall a childhood of exploring the woods and wondering why a plant grows where it does or how a bird knows where to build its nest. This same curiosity drives the Clifton team and their research projects with high school students, college students, university professors, environmental groups, the community, and government organizations.

Co-Directors Bert and Eleanor Harris

Founded in 1985 under a different name, The Clifton Institute has been around for 40 years, run by part-time employees. In 2011, the name changed to The Clifton Institute to reflect the environmental work being done on what was originally Clifton Farm. The Institute’s co-directors are husband-and-wife team Dr. Bert Harris and Dr. Eleanor Harris. “Eleanor and I had the idea that we could run a research station, but figured we’d find something like that out west,” Bert Harris says. “But this job popped up in 2017 and we both started in 2018.”

“As a kid, I started out as a bird watcher,” Harris shares. “Now, I’m interested in everything.” He studied at Sewanee: The University of the South in Tennessee. “The school was in a rural setting, so I started a nature club to get fellow students interested. It was inspiring to see people get excited,” he remembers. After earning his undergraduate degree in ecology and biodiversity at Sewanee, he earned a Ph.D. in ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Adelaide in Australia. He then completed a postdoctoral fellowship at Princeton University and is now an adjunct professor at American University and George Mason University.

Before coming to Clifton, Harris realized a lot of conservation biology is “published in papers that nobody reads.” However, “People can come out here, see all this biodiversity, and learn more about nature. We have events for all ages; last year, we had 3,000 students who came. And the research is exciting — we only pick super-targeted research projects that benefit how landowners can manage their land.”

Events include field trips for school groups, natural history lectures, walks with a naturalist, nature journaling, evening programs, and an annual Spring Native Plant Sale (scheduled for May 3 this year) where visitors can purchase plants grown from seeds collected and grown by Clifton staff. Programs are designed to encourage a sense of curiosity for visitors and provide education while having an overall positive impact on the environment. The Institute also has the biggest dataset in the world on kestrel movements, which is North America’s smallest falcon. Staff have documented 2,600 different species at the Institute and have a goal to catalogue every species on their property. “If people don’t know what we have, how can we help with conservation? That’s where the research comes in,” Harris adds.

Landowner Outreach Program: Kadiera Ingram

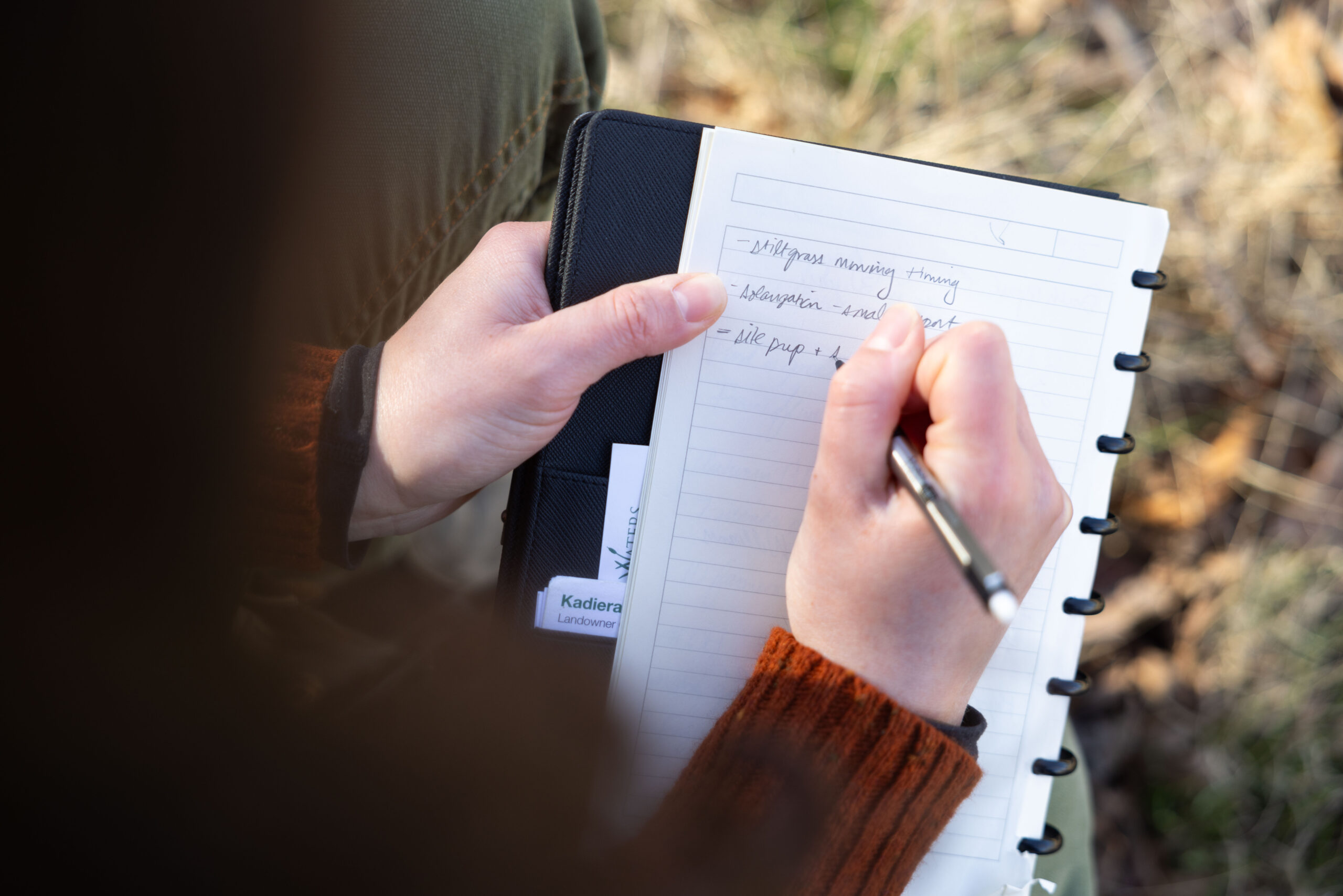

Kadiera Ingram serves as an associate of Clifton’s Landowner Outreach Program, visiting property owners in northern and central Virginia and Washington, D.C. Originally from Great Falls, now living in Hume, she earned her bachelor’s degree in biology from George Mason University in 2015 and started at The Clifton Institute in July 2023. Her role involves providing practical advice on how to manage land to benefit native plants and animals, with an emphasis on wildflower meadows and grassland restoration.

“A lot of people buy land out here and aren’t sure what to do with it,” Ingram says. But when Ingram sees people engage and make new discoveries on their land, it gets them excited about conservation.

There’s no one-size-fits-all approach to habitat restoration and land management, since every landscape is different and every owner has different priorities. However, after a walk of their property, Ingram will provide advice based on the landowner’s goals, which can include wildflower meadow establishment, native plant selection, invasive plant control, biodiversity-friendly grazing or hay production, native seed production, pollinator habitat, bird conservation, and wildlife management. Ingram shares, “My favorite moments have always been helping people discover something exciting about their own property, like a nice native plant community or a spot that has great potential… It’s so fun to see folks get excited about their land and see where that enthusiasm takes them.”

Ingram’s Best Practices for Biodiversity

Invasive plants crowd out and displace native plants. Getting them under control and preventing their spread is critical to protecting native biodiversity. Common invasive plants that pop up in local fields are the autumn olive, an invasive shrub, and the multiflora rose, which is a thorny, deciduous shrub. The problem with these plants is that because they come from foreign environments, they don’t have natural predators and spread fast, overtaking indigenous plants. “Native plants are absolutely necessary for supporting native pollinators, birds, and other wildlife,” Ingram explains.

Manicured lawns further reduce resources for wildlife. Taller, unmowed vegetation has value for native species in every season — even in the dead of winter. “If landowners are worried about things looking messy or neglected, we’ve found that maintaining a few thoughtfully placed pathways and mowed edges along the driveway can help the unmowed space look more intentional,” Ingram adds.

Finally, planting a wildflower meadow can be a great way to improve field quality for wildlife and pollinators, as well as creating something pretty. Ingram advises, “If you want a wildflower meadow, it’s a good idea to wait a growing season to see what already occurs.” Sometimes after allowing a field to grow up, landowners are surprised to discover a beautiful and diverse native wildflower meadow already in place. Taking stock of the existing plants before making a plan will save time, energy, and money, and ultimately goes a long way in ensuring the success of the meadow.

Ingram hosts in-person gatherings several times a year giving property owners a chance to gather, talk about their projects, and share triumphs and challenges. “We also hold workshops with topics on native seed collection and invasive species management,” she says. “These are held at Clifton in the old 1800s pink house — we actually call it the ‘peach’ house.”

The nonprofit invites anyone interested to become a Friend of the Clifton Institute by making an online donation. The property’s trails are also available for hiking on Saturdays from mid-January through mid-October.

Ingram reflects, “Growing up with nature, I took it for granted when it’s really something we need to actively protect. This realization felt like a call to arms and pushed me along the path that I’m on now. Where I live in Hume, you see these really old buildings and old-looking landscapes, and I think, what can we do to maintain them? It’s like we’re tapping into the heritage of the area.” ML

The Clifton Institute is located at 6712 Blantyre Road in Warrenton. For more information, visit cliftoninstitute.org.

Published in the April 2025 issue of Middleburg Life.