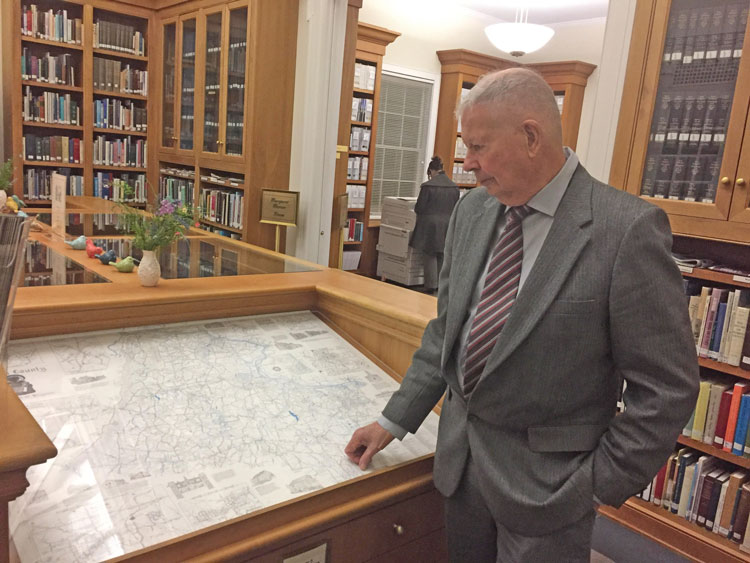

Eugene Scheel: historian, mapmaker, regional gem

Story and photos by Heidi Baumstark

Cultivating curiosity. That’s what historian and mapmaker Eugene Scheel does. He cultivates curiosity for inquiring minds.

Through an array of multicolored straight and curvy lines, his hand-drawn maps link one historic Virginia village to the next and create an intricate scene that tells the unique story of a place. Over a span of 45 years, Scheel has written nine books on Virginia history and his hand-drawn maps number in the hundreds ranging from poster-size to smaller images for articles and books.

All his material spurs a hunger for those wanting to learn more. And he delivers.

After completing his first map of Loudoun in 1972, he was commissioned to draw historical maps of other counties: Fauquier, Culpeper, Madison, Prince William and Rappahannock. Some of his maps and writings have included neighboring Warren and Shenandoah counties.

His work was published in journals, magazines, books and newspapers. He even drew the attention of the late movie star Elizabeth Taylor, who hired him to draw a map of Atoka Farm outside of Middleburg.

Born in the Bronx, Scheel earned his undergraduate degree in geography from Clark University in Massachusetts, a graduate degree in planning from the University of Virginia School of Architecture and a graduate degree in American literature from Georgetown University.

In 1965, he moved to the historic village of Waterford, Virginia, and worked for National Geographic. He currently remains in Waterford.

“National Geographic was at 17th and M streets in D.C.;” he said, “back then it took about 55 minutes to drive to work. There were only a few stoplights.”

He worked on their magazine, adding graphics like maps, graphs and paintings to stories; he was also on the story suggestion committee. In 1969, he left to be a consultant to Virginia Governor A. Linwood Holton for the office of state director of planning.

When it came to Middleburg, “I was the first person to write about the town’s black history; it was the center of black commerce and no one wrote about it,”

-Scheel

In 1972, Chuck Graves from the Loudoun Board of Realtors wanted a map of Loudoun County, which was established in 1757 from western Fairfax County.

“The last Loudoun map that was drawn was from 1922 and they wanted one with road names — not just road numbers,” Scheel remembers. “I decided to put a lot of detailed history with it, so I added the location of an old school or church and so on. They didn’t ask for that, but they got it.”

A real estate agent showed the completed map to Rosser Payne, a well-known planning consultant in Fauquier County. He thought it was a good idea, so Fauquier National Bank (now The Fauquier Bank) sponsored the project for Scheel to draw a historic map of Fauquier. It was completed in 1973.

Next, Tom Jones of Culpeper, an officer of Fauquier National Bank, wanted a map of his county. The Culpeper map was completed in 1975.

Local banks in the county in which the banks’ customers lived have funded many of his maps. When they came in for banking services, customers could also purchase a map.

From 1976 until 1981, the Loudoun Times-Mirror newspaper published over 100 of Scheel’s detailed history articles, which later were compiled into a five-volume book series called “Loudoun Discovered: Communities, Corners and Crossroads” (2003). The series totaled some 900 pages with folded and flat maps of about 120 Loudoun towns, villages and hamlets.

From 1999 until 2010, he wrote a history column for a local edition of the Washington Post and before that, the Washington Star.

Now, back to that one he made for Elizabeth Taylor. In the late 1970s, Scheel said, “Her secretary called and wanted to know if I could draw a map of Atoka Farm.”

This was during the period when Taylor was married to Virginia Sen. John Warner. Scheel was invited to their holiday party and was asked to present it to Warner as a Christmas gift from Taylor.

He uses a collection of colored pencils and pens with removable tips to create varying lines of thickness and a type of permanent ink, called India ink, to draw intricate road names, railroad tracks, streams, mountain ranges, family graveyards, Civil War battles, Indian burial grounds, schools, churches, post offices and distilleries.

His most recent map was completed in December 2016 featuring Short Hill, a mountain range east of the Blue Ridge in Loudoun County, which for the first time included another category: sites of airplane crashes.

To capture details often missing in regular historical accounts, Scheel gathers information from longtime locals.

“The old-timers want to talk,” Scheel said. “They’d say, ‘Let me tell you about Harry …’” Scheel would drive around in his Ford pickup and would meet with someone two or three times so he could fill in any gaps.

Scheel has taught and continues to teach a spring and fall course to Loudoun County history teachers and community members about various eras of Virginia history, connecting it to American history as a whole. Richard Gillespie, historian emeritus of the Mosby Heritage Area Association and retired Loudoun County history teacher, took one of Scheel’s courses in 1974.

“One of the sites he introduced me to was historic Ketoctin Church northwest of Purcellville,” said Gillespie. “I took my wife there on our first date and 18 months later, we were married in the 1854 church.” He also said that Scheel’s Mosby Heritage Area map is one of the association’s foremost resources.

When it came to Middleburg, “I was the first person to write about the town’s black history; it was the center of black commerce and no one wrote about it,” Scheel said.

His book, “The History of Middleburg and Vicinity,” published in 1987 for the 200th anniversary of the 1787 founding of Middleburg, is a serious account of the area’s heritage and its founder Leven Powell (1737-1810), an American Revolutionary War lieutenant colonel and Virginia statesman.

But how Colonel Powell got the town established had a unique twist. He sent a petition to the Virginia General Assembly and got several of his war comrades from Pennsylvania to sign it.

“The petition has all these German names on it; they didn’t even live here so they weren’t on the Virginia census,” said Scheel.

Since the big mill in nearby Aldie, Virginia, made it a significant place of commerce, Powell — a wealthy landowner — wanted to turn Middleburg into a prosperous, well-known town.

Judith James, of Strasburg, was visiting the Thomas Balch Library one evening in March when she introduced herself to Scheel who was visiting the library. She was researching the 1867 Shiloh Baptist Church in Middleburg; the church recently celebrated their 150th anniversary. James said, “His work is unbelievable. His book on Middleburg is a main source for my research.”

“Putting almost-forgotten villages on maps has led many to be far more interested and therefore, become stewards of them. He has advanced our knowledge, understanding and interest in this region. That’s why he’s a regional gem,” said Gillespie.

Maps or books can be ordered directly from Eugene Scheel by writing him at P.O. Box 257, Waterford, VA 20197 or calling him at 703-727-2946. ML