Then & There Flush With Love: A Jealous Heart and a Stolen Dog

Photos and story by Richard Hooper

During the courtship of Elizabeth Barrett by Robert Browning, there was one ever-present witness to their love story — Flush, Elizabeth’s beloved Cocker Spaniel. Flush did not like what he saw.

Flush did not like Barrett’s distraction as she awaited Browning’s letters (the post could arrive 12 times a day in Victorian London) or her intense concentration on something other than himself as she penned hers back to him. That was almost as bad as the time she spent immersed in writing those secret poems. Sonnets she called them.

Worst of all, though — it was nearly unbearable! — was to hear Browning’s footsteps as he ascended the stairs to Barrett’s third floor room and to know that now he would be so ignored that he might as well not even be there.

It was his room, too. As a matter of fact, Barrett herself was his as well. As Barrett’s trusted companion, now in the self-appointed role of chaperone, Flush was being forced to witness a strange and threatening bond growing between Browning and Barrett.

He had endured these torments for more than a year. Enough was enough. This could not continue.

So, on one fine day in early July 1846, his reservoir of patience no longer confined by his breeding, Flush took matters into his own teeth and viciously bit Browning.

Barrett had received Flush five years earlier from her good friend and fellow writer, Miss Mary Russell Mitford. The affection between Barrett and Flush grew rapidly. Barrett believed that Flush was gifted with unusual intelligence and endeavored to teach him the alphabet so that some day he might read, which would help Flush understand the board games Barrett was teaching him to play.

Flush’s meals of cakes, custards and scraps of meat (beef — Flush did not like mutton and his bread had to be thickly buttered) came almost exclusively from Barrett’s hands. As Barrett wrote in one of her two poems about Flush, “feast-day macaroons / turn to daily rations.”

Barrett’s doctor did not approve of Flush sleeping on the sofa with her, so Flush received a daily bath. Yes, Flush was spoiled and Barrett’s brothers and sisters, the household staff and the bloodhound, mastiff and terrier that also resided at 50 Wimpole Street were not above expressing their disgust.

Accustomed to getting his way, Flush was no doubt flummoxed, when Browning, even after being bitten, continued to visit. Three weeks after issuing a fair warning, Flush bit him again.

Browning had tried to be friends with Flush by bringing him cakes and other treats. Flush, however, was blind to Browning’s entreaties, and saw him as the cause of Barrett’s estrangement and agitation, which had lately been increasing. Flush did not know that Browning and Barrett were on the verge of implementing their secret marriage and moving to Italy.

Flush was, though, pleased by the more frequent outings with Barrett. Her physical condition had improved through her love for Browning and his for her. It was on one of these jaunts that Flush was stolen from her — for a third time.

The first theft had occurred in 1843. Barrett’s autocratic father wanted to bargain with the thieves over the ransom and refused to pay the full demand. Barrett, however, arranged for full payment to be made in secret. For the first time in her life, at age 37, she had defied her father’s wishes.

But now, less than two weeks away from her marriage, Flush was again stolen. Negotiations had to proceed swiftly and were undertaken by a desperate Barrett who traveled by carriage to the thieves’ stronghold in Whitechapel (later the scene of Jack the Ripper’s grisly crimes). Flush was held for six days before a ransom was settled upon and paid. He was returned just five days before Barrett’s wedding.

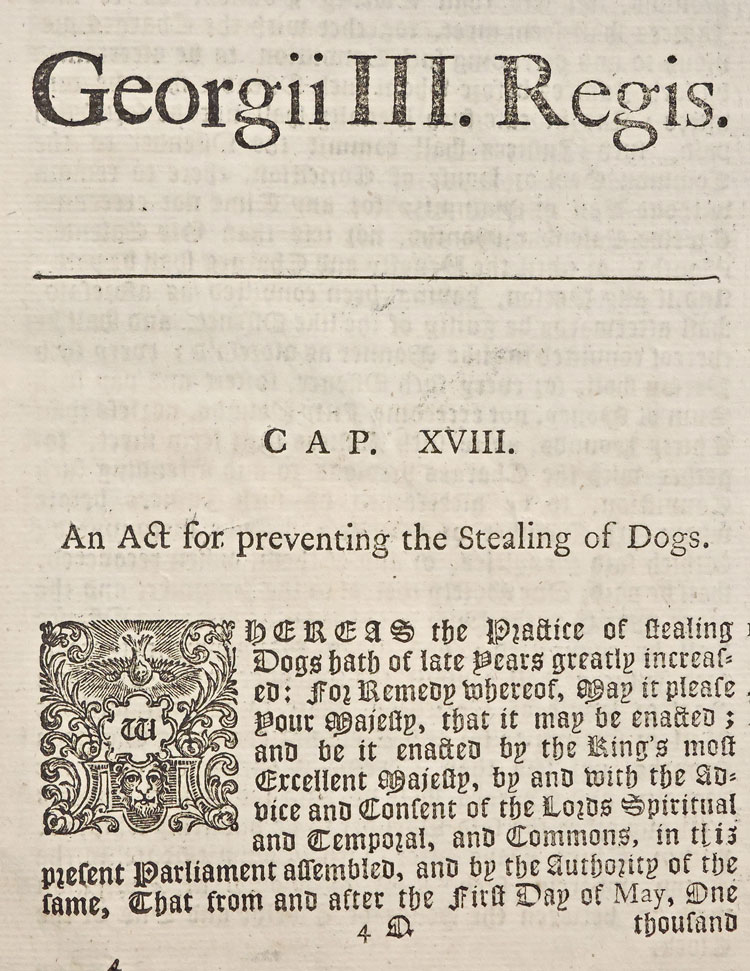

There were laws against the theft of and trafficking in stolen dogs. There was an act against such practices in 1770, another in 1827 and still another in 1845. They were, however, generally ignored and owners feared for the safety of their pets if the police were brought to bear.

Browning and Barrett did not include Flush in their brief, secret wedding ceremony. A week later, though, he did go with them to their new home in Italy. Flush softened toward Browning and long walks together became a coveted routine.

In any portrayal of Elizabeth Barrett, Flush was a necessary character. In the 1934 movie, “The Barretts of Wimpole Street” Flush was the first character we met as he walked along Wimpole Street. The movie was an adaptation of the play that opened on Broadway in 1931.

The play had an extensive run and the same canine thespian portrayed Flush in every performance. He never missed a cue, except for opening night when he jumped into the audience, prompting an ailing “Elizabeth” to leap up from her sofa to fetch him back onstage.

Virginia Woolf wrote a biography of Flush illustrated by her sister Vanessa Bell. Although not widely read today, it was a best-seller when it was published in 1933.

In her poem “To Flush, My Dog,” the same poem quoted above, Elizabeth wrote:

Therefore to this dog will I,

Tenderly not scornfully,

Render praise and favour!

With my hand upon his head,

Is my benediction said

Therefore, and for ever.

Richard Hooper is an antiquarian book expert in Middleburg. He is also the creator of Chateaux de la Pooch, elegantly appointed furniture for dogs and home. He can be contacted at [email protected]. ML