Foxcroft School’s Garden Legacy Project: Friendship, Founders, and Flowers

Written by Bill Kent

Foxcroft School’s 500 acres are shrouded by tall, sheltering woodland. One place on campus offers a Hunt Country vista so stunning that students, faculty, and visiting parents cannot help but pause and take it in.

The view from the Library Courtyard faces south, framed by a low stone wall that reveals the grand oval of the school’s riding track. A prim, gabled guesthouse, the Spur and Spoon, sits behind it and could stand in for a country house. Behind that, the Bull Run mountains rise in the distance, rugged and verdant.

Two waist-high bronzes of a fox and hound flank the courtyard scene. They represent two student teams established by the school’s founder, Charlotte Haxall Noland. On a day known as Choosings, each student joins a team and competes on horseback and in other sporting activities as part of a rigorous educational regimen that’s shaped the lives of future politicians, scientists, artists, Olympians, actresses, writers, CEOs, philanthropists, and more during their time at Foxcroft. Among them was the renowned landscape architect Rachel Lambert “Bunny” Mellon, designer of the White House’s original Rose Garden and other notable horticultural installations throughout the world.

In 1989, while living at Oak Spring, the Upperville farm and garden she shared with her second husband, philanthropist and equestrian Paul, Mellon celebrated Foxcroft’s 75th anniversary by designing and installing the Library Courtyard.

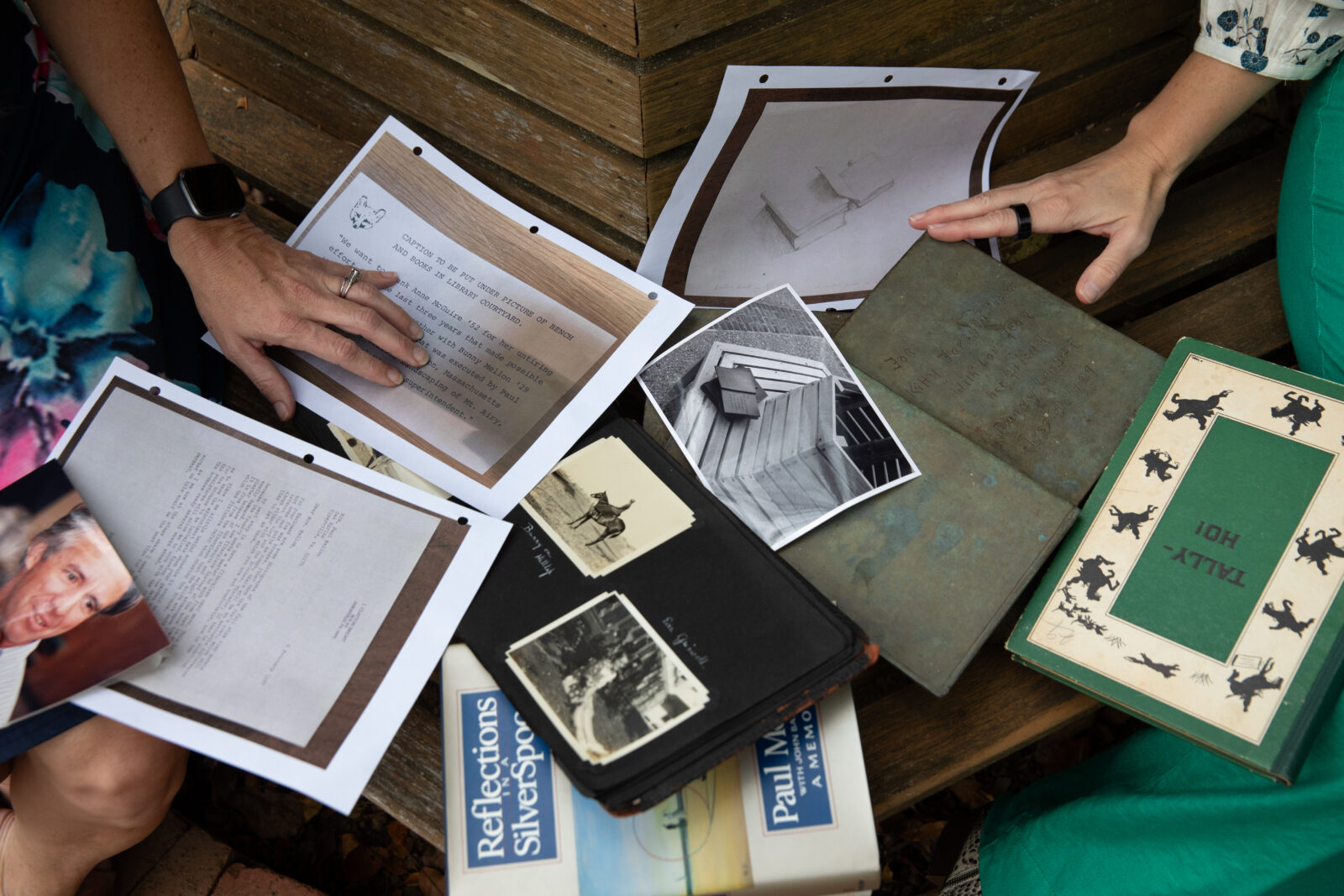

Mellon’s work on the Library Courtyard and Miss Charlotte’s Garden represents far more than a caring gesture from a grateful student. Earlier this month, Foxcroft faculty members Julie Fisher and Dr. Meghen Tuttle presented their Garden Legacy Project at the Henry Morrison Flagler Museum in Palm Beach, Florida. The culmination of three years of research at Foxcroft and the Oak Spring Garden Foundation Library, their work explored the ways Noland’s educational and horticultural ideas shaped Mellon’s. The project, funded by the William R. Kenan Jr. Charitable Trust, documents how Noland and Mellon went on to change the way American women saw themselves in their gardens, in nature, in their professions, and in the world.

Fisher, director of Foxcroft’s STEAM Program, shares, “We embarked on the Garden Legacy Project to tell the stories of these courageous, creative, and compassionate women. We also endeavor to embody the same understandings they set forth over a century ago.”

Noland and Mellon “were born into privilege, neither attending college yet both groundbreaking in their respective fields of education and design,” Fisher says. “They shared not only a love of gardening, but an understanding of and appreciation for the greater scope of the natural world and its transformative role for the individual and the community at large.”

Born in 1883, Noland grew up at Burrland in Middleburg. She loved the great outdoors and riding, and would become a co-master of the Middleburg Hunt. At Harvard’s Sargent School, she learned to teach physical education and was introduced to the sport of basketball. Noland taught in Baltimore and at The Bryn Mawr School before founding Foxcroft School in 1914. She named it after an estate she glimpsed while traveling in England that belonged to Major Foxcroft. For Noland, Foxcroft was meant to be a place that girls would want to attend. The school’s motto is “mens sana in corpore sano” — a healthy mind in a healthy body.

Miss Charlotte, as she became known to her students and faculty, lived in the Brick House, which was built by her ancestors in the 1700s. She worked the land with her students, including a terraced garden behind the house, which features a towering magnolia tree. A cofounder of the Loudoun and Fauquier Garden Club, she inspired students to make what Tuttle, who teaches science in Foxcroft’s STEAM Program, calls “connections between themselves and the natural world” in the school’s wooded areas. Creating a World War I Land Army Garden, as well as a World War II Victory Garden, became a lesson in sustainability and community service.

Tuttle adds that “other schools at the time might have taught girls flower arranging. At Foxcroft, Miss Charlotte used place-based learning to teach botany in a way that prefigured our contemporary ideas about ecology, environmental science, and biodiversity.”

As a young girl, Mellon became fascinated with gardening while watching the Olmsted Brothers — sons of America’s first landscape architect, Frederick Law Olmsted — design the plantings around her family’s Princeton estate. The daughter of the Gillette Safety Razor Company’s president, she wanted to go to Foxcroft as soon as she heard about it.

Mellon was given a small area to garden in, though its exact location is not known. She developed a friendship with fellow student Kitty Wickes. When they graduated, Wickes and Mellon went on tours together of famous gardens in Europe. Later, during her design of the Library Courtyard, Mellon wanted to memorialize her friendship with Wickes. She surrounded an apple tree with a small bench, on which rests a bronze sculpture of a stack of books commissioned from Pennsylvania artist Clayton Bright. A dedication to Wickes is inscribed on an open page: “With love from her friend, Bunny Lambert, Class of 1929.” Mellon also directed Bright to make the Library Courtyard’s iconic fox and hound statues.

Though she rarely gave interviews, when asked about her gardening style, Mellon said, “Nothing should be noticed.”

Sometimes, however, things were noticed. Among Mellon’s additions to the White House grounds, at the behest of John F. and Jackie Kennedy as well as Lady Bird Johnson, was a magnolia tree similar to the one that shades Miss Charlotte’s Garden at Foxcroft. It was deemed controversial at the time, because this was a native tree and not considered worthy of the exotic specimens that vied for the president’s attention.

Mellon’s plans for the Library Courtyard, created in conversation with Foxcroft alumna and trustee Anne Kane McGuire, involved the creation of a focal point for the school, an outdoor classroom that would convey Miss Charlotte’s original, lasting ideals: that art, education, physical activity, and the great outdoors are the path to confidence, responsibility, and humility.

“Bunny never forgot her experiences at Foxcroft,” Fisher adds. “On the walls of her library at Oak Spring is a Rothko; Bunny loved Rothko’s art and collected many of his works. Opposite the Rothko is a photograph of Miss Charlotte.” ML

Featured photo by Lauren Ackil Photography, courtesy of Foxcroft School.

Published in the March 2025 issue of Middleburg Life.