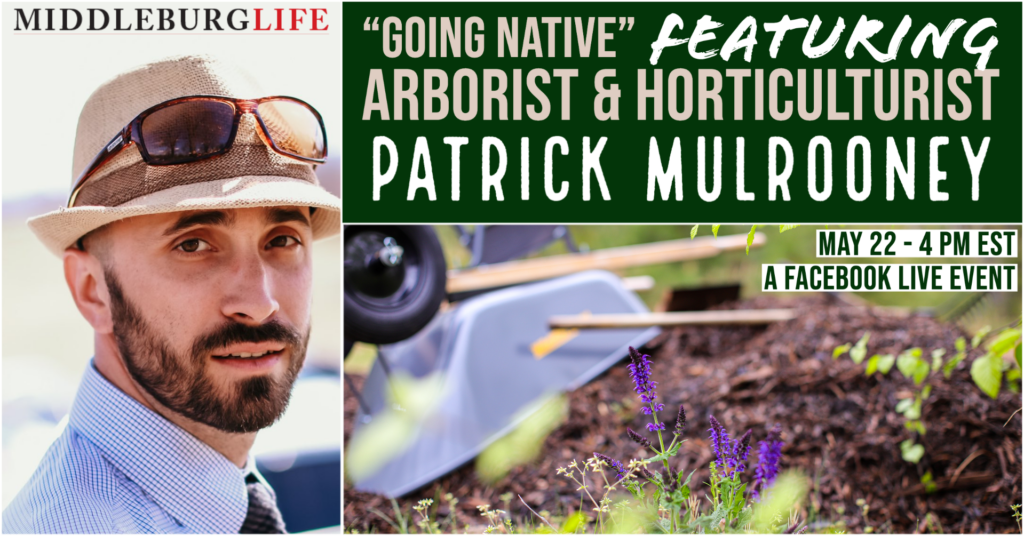

Going Native: Not Why, But How

Written by Patrick Mulrooney, ASHS Certified Horticulturist, ISA Certified Arborist | Photos: Joanne Maisano

As temperatures rise, the month of May presents itself as the last opportunity to install plants before the heat of summer, so why not give back to the environment and go native?

We already know development has fractured natural habitats and that birds, one of our best ecological indicators of environmental health, have declined by about one-third of their population in the last 50 years, pointing to the notion that the insects and plants that feed this upper level of the food chain are threatened. Creating habitat in our own yards is oneway to create habitat “corridors” that allow native animal populations to travel to and from food sources.

Since native gardening is becoming more popular and there is no shortage of articles explaining why to do it, I wanted to set this one apart by offering a more specific set of guidelines about how to do it. We will discuss some of the common non-native plants and let you know good natives to use instead, while discussing the habitat benefits of “nativars” (native varieties), a somewhat new concept too.

Catawba Rhododendron

To pick on one of the most overused landscaping plants, I will first set my sights on nandina, an East Asian plant gradually being added to invasive plant lists across an ever-growing number of states. Aside from its invasive growth habits, it produces toxic berries which contain cyanogenic glycosides that have been known to poison pets and birds. To replace this brightly colored evergreen, you could use Catawba rhododendron (Rhododendron catawbiense) or a mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia), both of which are evergreen like the nandina.

The dwarf varieties and the slow growth rate of these two plants make it comparable to the nandina for landscape purposes. However, it is the resources they provide to bumble bees and butterflies which makes these plants far superior for creating habitat. Other substitutes include inkberry holly (Ilex glabra), winterberry(Ilex verticillata) and leucothoe (Leucothoe fontanesiana), which offer many resources for birds, butterflies and bees. Other widely used but resource-poor shrubs are cypress and Japanese holly.

Better native choices would include oak leaf hydrangea (Hydrangea quercifolia), Carolina allspice (Calycanthusflorida) or one of our many native viburnums. These three plants offer pollen and nectar; additionally, the allspice is a favorite food source for many native sap beetles, which feed on the pollen and pollinate the flower. How is that for diversity? A beetle-pollinated shrub?

Oakleaf Hydrangea

When choosing native plants, it is possible to inadvertently purchase beautiful varieties that produce sterile flowers, which offer little to no benefits to wildlife. I made this mistake when I purchased my ‘Snowflake’ Oak leaf Hydrangea; however, the double flowers are so gorgeous I am not complaining. The Carolina allspice variety ‘Aphrodite,’ which is a hybrid between our native species and the Asian species, does not seem to have this problem, as bees and butterflies are regular guests at the two shrubs in my backyard.

More research must be done on how these native cultivars, or ‘nativars,’ as they are commonly called, differ in their production of pollen, nectar, and fruit. For instance, one study saw a three-to five-fold decrease in insect foraging on nativars that were bred to have red, blue or purple leaves. The theory is that pigments in the leaves produced chemicals that were distasteful to insects. This illustrates the unforeseen reactions that may take place within the plant when breeding to create new plant varieties.Tired of your crape myrtle? Try installing a service berry (Amelanchier spicate) or hawthorn (Crataegus spathulata.) in its place.

Ostrich Fern

The trees offer berries to birds and the leaves are a larval host to many moths and butterflies. Frustrated by the rapid growth of your Bradford pear? Try an American holly (Ilex opaca); it will grow at a moderate rate until it reaches a height of 15 – 40 feet while offering shelter and food to native birds. Also consider the redbud (Cercis canadensis), or dogwood (Cornus florida), which benefit both pollinators and butterflies. Another effective strategy when creating habitat is to choose native plants that can be aggressive and will spread through your garden without much help. In the still-forested back corners of my yard, invasive honeysuckle vine and multiflora rose still have a good foot-hold.

To help out-compete these bossy weeds, I have added several dozen ostrich ferns (Matteuica struthiopteris) and celandine poppy (Styllophorum diphyllum), both of which have proven to be one hundred percent deer-proof. In addition to adding beauty to the war-scape of thorns and tangled vines, the ferns are a larval host for the ghost moth (Sthenopis pretiosus)and the poppy produces seed pods which are a great food source for chipmunks! Who doesn’t love a good chipmunk?

Celandine Poppy

After a few seasons of growth in the leaf-litter, and with the help of other natives that are naturalizing quite well (may apple, Virginia bluebells, white wood aster) these plants will form a blanket over the forest floor, creating habitat and moist, shaded conditions for animals and insects, as well as for plant roots.

There are so many benefits to going native in your garden, each plant offering a small list of services. Whether it is a lush blanket of fern fronds to shelter small animals and plant roots, a fresh bloom of spring flowers laden with nectar for emerging insects, or a vital set of fruit that only ripens during the dire winter months, all play crucial roles for something in our ecosystem.

While it maybe overwhelming to keep track of all these facts, we can unburden ourselves of this study by just remembering that our native animals co-evolved with our native plants, and over millions of years, bound their survival together. As we sometimes forget, nature has it figured out for us. All we have to do is plant native and encourage diversity. ML

This article first appeared in the May 2020 issue of Middleburg Life.