Then & There The Great Foxhound Match

Story and photos by Richard Hooper

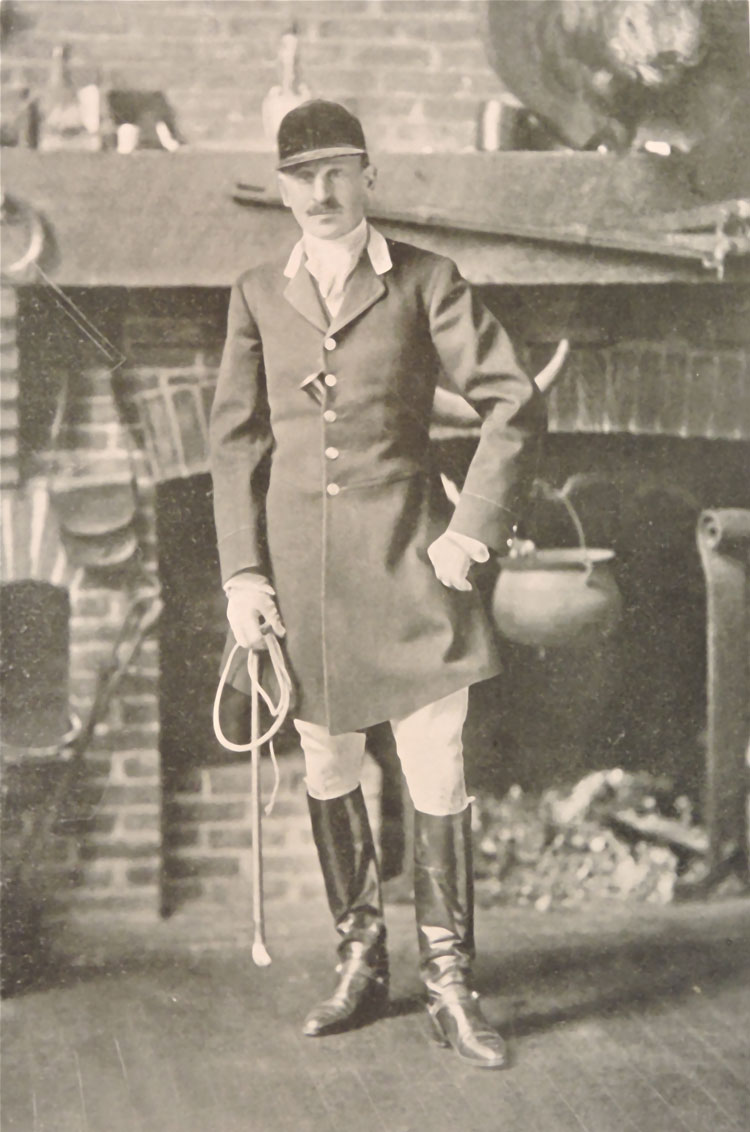

It was a huge event, both sporting and social. The two-week contest between Harry Worcester Smith’s American foxhounds and A. Henry Higginson’s English foxhounds promised to be a pivotal event settling the debate on which was the better hound. Both men were current masters of hunts that they had established: the Grafton Hounds for Smith and the Middlesex Hounds for Higginson.

The contest derived from a series of letters by Smith, Higginson and Higginson’s friend Julian Ingersoll Chamberlain that began appearing in January of 1905 in the sporting journal Rider and Driver. The letters continued until challenges were extended and accepted. Bets were laid, and it was agreed that the contest would take place in Virginia’s Hunt Country with epicenters of Middleburg and Upperville. Because both Smith’s and Higginson’s hunts were located in Massachusetts, this was considered to be a neutral territory. Each pack was to hunt a total of six times on alternate days. It began on the first day of November, 1905, at Welbourne, about midway between the two towns.

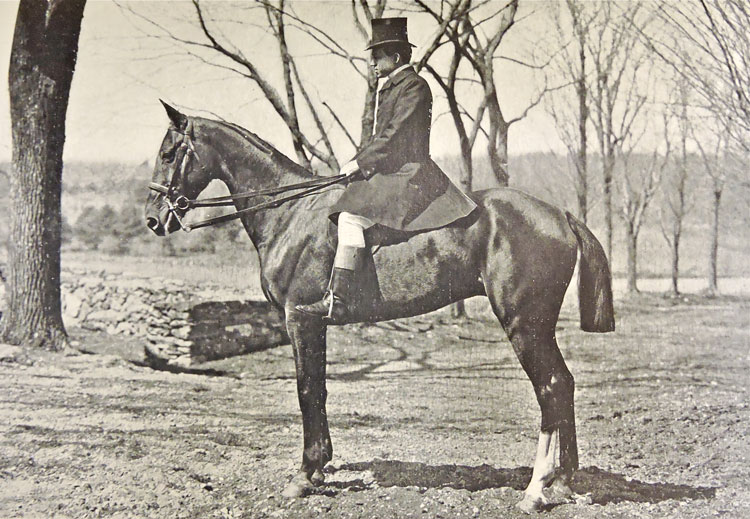

Horses, hounds, masters, hunt servants, grooms, the press, judges of the match and men and women looking for good hunting and a chance to observe this momentous occasion had made their way by train, switching to carriages and horseback for the final leg to their accommodations. On the first day, there were members of some 26 hunts from the United States and Canada. The ranks were swollen by locals who, of course, were waiting with great anticipation.

Smith was advocating for the establishment of a breed standard for the American foxhound, arguing that it was a more capable hound at chasing the fox in America. Among its other qualities, he believed in its independent hunting ability, voice and speed.

Higginson, cutting to the chase (so to speak), did not believe that an American foxhound even existed. To him a pack of six couples of “so-called American hounds” could look like 12 different breeds. Twenty-five years later, they still were being derided by Irish author and MFH Edith Somerville, who thought that an Irish setter, “neatly shaved, and the permanent wave obliterated,” might pass as an American foxhound.

“There is no animal in the world, not even the horse, that has had as much attention paid to its breeding as the foxhound has had in England,” wrote Frank Sherman Peer in “Cross Country with Horse and Hound” in 1902. It was a system and history that Higginson ascribed to. In his mind there was no room for improvement. Higginson wanted his hounds to hunt as a tight pack. He believed in uniformity in appearance (something that Smith was actually breeding for) but to such an extent that observers at the match could not distinguish one of Higginson’s hounds from another. In both appearance and method, it was something akin to a regiment of British redcoats in tight battle formation on one hand and a bunch of colonialists skirting from tree to tree on the other.

The Middlesex Hounds hunted first. Higginson had two broken ribs and did not hunt that first day. Smith broke a bone in his foot on Day 3, while following Higginson’s pack, but he continued to hunt each day. The ladies hunted aside. However, on the fourth day for Middlesex, Mrs. Tom Pierce, a friend of Higginson’s, came out riding aside. As luck would have it, she crashed and broke a tooth. Undaunted, she summoned for a backup horse and continued after hounds.

It seems as if anyone could have joined the field. The same day that Mrs. Pierce had her accident, the hounds ran past a farmer patching his roof. Unable to resist the lure of the music, he scrabbled off the roof, saddled his horse and took off in pursuit.

Amid all the sport and entertainment, the sideline of horsetrading was flourishing and, as usual, not without incident. Courtland Smith, Harry’s brother who was not hunting because of a broken collarbone, brought suit against both Higginson and Mrs. Pierce regarding horse transactions. In addition, Higginson was fined for trespassing.

As to hounds, Smith’s contingent thought that the English hounds were slow and lacked initiative, while Higginson’s camp thought the American hounds were undisciplined, no better than if they had run riot. After all, on Grafton’s first day the American hound’s enthusiasm took them so swiftly away from the field they were neither seen nor heard for over two hours.

The rules stated that the pack that killed a fox would be declared the winner. Alas, the only fox that was killed had been someone’s pet, and there was a question as to whether this had been an accident or a deliberate plant intended to fix the outcome.

It was judged not to count. Since no wild fox had been killed, it was up to the judges, who had been appointed before the match to each side’s satisfaction, to determine the outcome. So, who won?

After the last day’s hunt, participants and observers met at Welbourne, where a decision by the team of judges would be declared. With so many factors to consider, they took their time that evening in reaching a conclusion. In the end, they declared Smith’s American foxhounds the winner.

But with the acrimony that existed between Higginson and Smith, it wasn’t really over.

In 1907, due to the driving force of Harry Worcester Smith, the Masters of Foxhounds Association of America was formed and Smith became its president for several years. He was followed by none other than Higginson.

It was under the auspices of Higginson that the association produced its first stud book in 1915, The English Foxhound Stud Book of America listing only English foxhounds. It was not until the fifth volume in 1930 that it became The Foxhound Kennel Stud Book of America, the first to list American and crossbred foxhounds as well as the English. ML

A very lively and detailed narrative of the match can be found in “The Great Hound Match of 1905” by Martha Wolfe, Lyons Press: 1916. As well as the books mentioned above, the Harry Worcester Smith Archives at the National Sporting Library & Museum, “The Story of American Foxhunting” by J. Blan van Urk, Derrydale Press: 1941 and “The States Through Irish Eyes” by Edith Somerville, Houghton Mifllin Co.: 1930 were consulted.