Then & Now, Some Stable Facts & Fancies

Story and photos by Richard Hooper

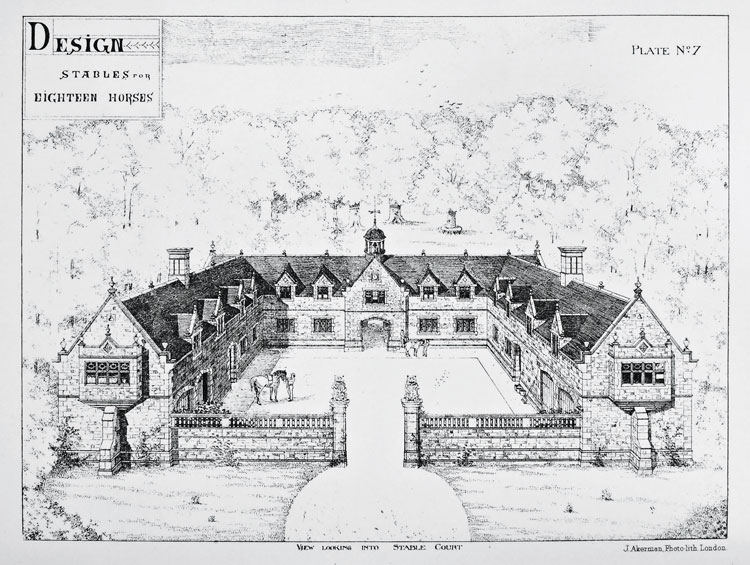

The essential function of a stable is always the same — to contain horses in a safe, hygienic environment with dry floors, good ventilation with accessible food and water — but the architecture of accomplishing this end varies wildly. It can, and has been, anything from the classical to the ultra modern and from the baroque to the rustic. Stables encompass a full range of architectural styles and ethnic and nationalistic influences: Georgian, Moorish, Italianate, Victorian, Gothic and Middle Eastern, to name a few.

On its most basic level, a stable can be erected in a fairly short period of time: a few enclosed stalls plopped down on the ground with little or no regard to appearance. However, if one believed that one would be reincarnated as a horse, one might wish to put a bit more thought and time into the process of creating one’s future abode.

Such was a motivating factor for Louis Henri de Bourbon, the seventh Prince de Condé, when he commissioned the construction of his fabled stable at Chantilly, France. He approved the drawings in 1719. Construction that began in 1721 was completed in 1736.

The stable was over 200 yards long and included room for 240 horses along with a kennel for 500 hounds. Its vaulted, 45-foot high ceiling provided ample ventilation. It is uncertain, though, if he ever took up residence.

Stables are usually thought of as a building in a pastoral, country setting on a farm or on an estate. If you visualize a Western setting, then it is on a ranch. Some of the largest examples, though, used to be in the great cities.

Horses were vital for public transportation and the apex was reached during the 19th century. Giles Worsley described the London scene in his book “The British Stable,” where, in the 1890s, there was a horse-drawn bus for every 350 people and the largest bus company, the London Omnibus Co., had 10,000 horses to accommodate.

Ideally, a company could locate a stable at the end of a route on the outskirts of the city, where land was less expensive and the stables could spread out and remain a single story structure. However, the other end of the line could be inside London, which necessitated stables with additional levels. The Road Car Co., for instance, stabled 700 horses on two stories and a yard that held 60 buses.

Horses not only moved people, but goods as well, and the most convenient location for the drayage companies to stable their horses was close to the railroad terminals, where space limitations inspired several stables of three stories. One such stable was the Mint stable located near Paddington Station. Its construction was completed in 1893 and it held about 600 horses distributed over three floors aboveground in addition to a basement.

Much care and consideration was afforded the horses by most of these establishments and Worsely stated, “In London in the 1890s, horses were probably better looked after on a large scale than at any time in history.”

The introduction of gasoline-powered vehicles began a decline in the mass use of horses and the end came rather quickly. There were 13 motorbuses and 3,623 horse-drawn buses in London in 1903. Ten years later, there were 3,522 motorbuses and 142 buses pulled by horses.

In August 1914, the few horses that remained pulling public transport were requisitioned for duty in World War I, essentially putting an end to vast urban stables. With a few exceptions, stables are now almost completely located in the countryside.

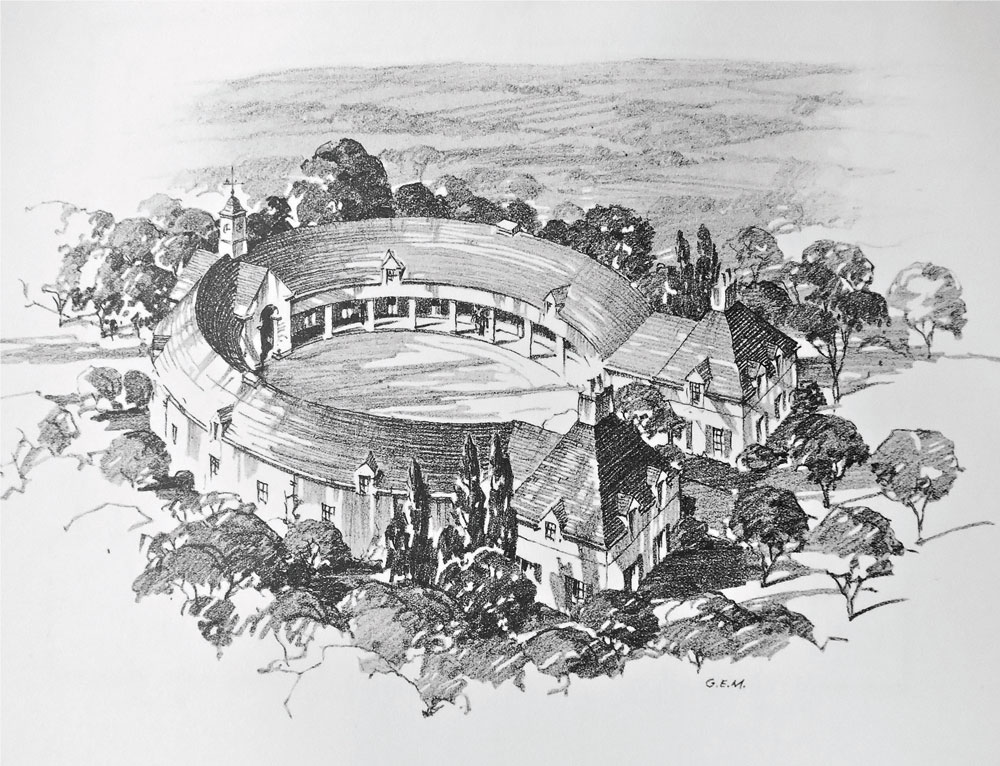

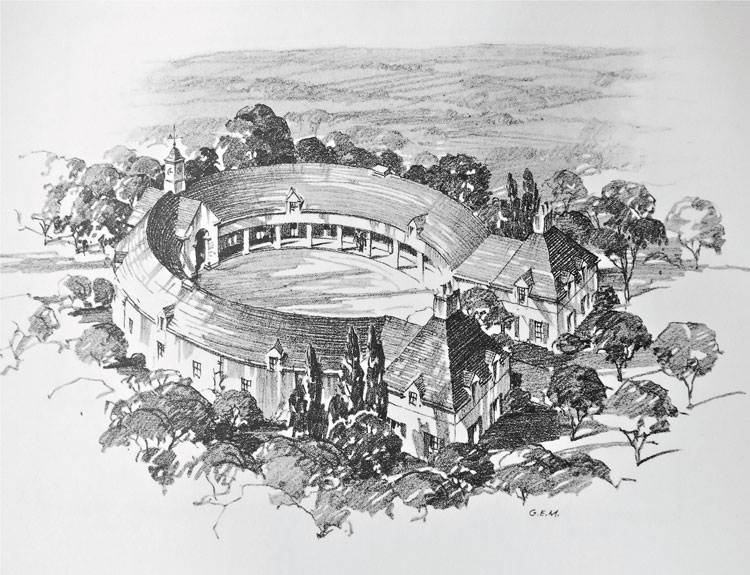

A stable can come in many shapes. It can be a few enclosed stalls to a long stretch of a building with either a single row of stalls or doublewide with a center aisle. It can also form the structure enclosing a rectangular courtyard or curving into the shape of a horse’s shoe.

There is a bird’s-eye view drawing of a horseshoe-shaped stable in the book “Sporting Stables and Kennels” by Richard V.N. Gambrill and James C. Mackenzie published by the Derrydale Press in 1935. The authors state, “There is very little to say about this plan for a horse shoe stable. I know of only one stable which resembles it in any way, and that has worked out very satisfactorily.”

In a book loaded with illustrations of stables identified by their prominent owners (F. Ambrose Clark, Winston Guest, Richard Mellon, C.V. Whitney, etc.) and prestigious locations, it is a bit curious that the authors did not identify the location of the one in the shape of a horseshoe. Hint: it’s not far from Middleburg. ML