Rectortown Slave Becomes Poster Child for Abolitionist Movement

Written by Heidi Baumstark

When one door closes, another opens. That’s true for slaves in Rectortown who were freed after the murder of their master Charles Rufus Ayres. The fatal day for Ayres was Friday, Nov. 11, 1859. The place was Rectortown, Va. The killers? Locals William Wesley Phillips and his oldest son 18-year-old Samuel C. Phillips.

The reason? An argument over a farm gate. According to an article in the Alexandria Gazette (Nov. 17, 1859), the quarrel between Ayres and William took place that November afternoon about 2 p.m., when the parties casually met in the public road near Ayres’s residence. It started as a misunderstanding about a farm gate that escalated into a verbal dispute using “very offensive language,” the article points out. Then the parties departed.

But before sundown, William and Samuel came riding through Rectortown — armed and ready — hunting for Ayres. Not finding him in town, they proceeded about three-quarters of a mile to Rectortown Station near the railroad tracks; the elder Phillips went into Rector’s Store/Warehouse built by Ayres’s stepfather, Alfred Rector. Not finding him there, William remounted his horse and the two retraced their steps back to Rectortown.

Rector’s Store/Warehouse built 1835 by Alfred Rector (Civil War Trails marker in front and circular yellow railroad crossing sign in back). Photo by Heidi Baumstark

Finally, they discovered Ayres inside Andrew Cridler’s shoemaker shop where shots were fired by Ayres and then by the elder Phillips. Ultimately, Ayres was struck a fatal blow, first shot by William and then by his son. Ayres “fell and died, in the space of two minutes,” the 1859 article states. The two Phillips men killed Ayres one month before his 33rd birthday. And they were arrested and sent 15 miles south to Fauquier County Jail in Warrenton.

Ayres was laid to rest Sunday, Nov. 13, 1859 in the “church-yard of the village, followed by a large concourse of sympathizing friends and relations.” Funeral services of the Episcopal Church were performed by Rev. Mr. Shields. The article ends with, “In life, he possessed many noble virtues, his death was an exemplification of one of them.” The church no longer stands, but Rectortown Cemetery on Maidstone Road (Rt. 713), is still there, believed to be where Ayres is buried (though no tombstone has been found) along with many Rectors, including the village’s founder, John Rector (1711-1773).

The events after the killing are where this freedom story starts. For who? For Ayres’s slaves and the several children he fathered with three of his slaves. But little did Ayres know that one of his own daughters — Fannie (also seen as “Fanny”) — would literally become the poster child for the abolitionist movement.

Who was Charles Rufus Ayres?

Born in Fauquier County on Dec. 23, 1826, he was the only son of Charles Wesley Ayres and Catherine “Kitty” A.M. Floweree. He was orphaned as a young child. When he was 11, his widowed mother married Alfred Rector in 1837, a prosperous merchant for whose family Rectortown was named on land owned by village founder, John Rector of German origin. Originally called “Maidstone,” Rectortown was established in 1772 by an act of the Virginia General Assembly and holds the distinction as the oldest town in Fauquier, located in the rural northeastern part of the county about four miles north of Marshall.

In 1843, at age 17, Ayres attended Yale University for one year. From 1847 to 1849, he attended the University of Virginia and was educated as a lawyer. However, he preferred the life of a farmer and was a prosperous landowner of 500 acres that surrounded the village of Rectortown. His farm included Milan Mill, on Rectortown Road (Rt. 710) and adjoined Rector’s Store/Warehouse located at the intersection of Maidstone Road (Rt. 713) and Lost Corner Road (Rt. 624). When the Manassas Gap Railroad came through in 1852, this 1835-built structure was added onto, housing the railroad station and post office, and still stands today. (During the Civil War, this building was used as a prison for captured Federal troops as shown on a nearby Virginia Civil War Trails marker. This marker includes text stating that the building was headquarters for Union General George McClellan when President Lincoln relieved him of command of the Union Army in November 1862.)

Although a Union man, Ayres owned slaves — at least 12 — according to his estate records. In an article in the winter 2015 issue of Fare Facs Gazette (historical newsletter for Fairfax City), the author writes that though unmarried, Ayres “took full advantage of the relationship and had at least three children by his slaves Mary Fletcher, Jane Payne, and Ann Gleaves. However, unlike most slaveholders, he acknowledged them and provided for them in his last will and testament.”

In his will dated July 28, 1857, Ayres freed all three women and their children, providing “five hundred dollars, or some sufficient sum of money, for their settlement in a free state.” The will stipulated that the two oldest children of Mary Fletcher — Viana (spelled “Vianna” in his will) and Sallie (sometimes spelled “Sally”) — plus the oldest child of Jane Payne and Ann Gleaves, would each receive after reaching the age of ten, “one hundred dollars annually a piece, to be applied in raising and educating them.” (At the time of his 1857 will, Fannie is not mentioned since she was born the following year.)

A Look into Virginia Law

A Virginia law passed by the Virginia General Assembly on Jan. 25, 1806 required that manumitted slaves (slaves released from slavery) and free blacks must leave the state “within twelve months” unless they petitioned the Virginia General Assembly to remain. If emancipated slaves remained in the state more than twelve months, they “shall forfeit the right to freedom and be sold.”

Many manumitted slaves chose to remain in the neighborhoods where they were known instead of leaving spouses, children, and other family behind, petitioning for permission to stay in Virginia. Additionally, on Feb. 18, 1856, the Virginia General Assembly passed an act providing for the voluntary enslavement of “free Negroes of the Commonwealth,” allowing free blacks to enslave themselves to a master of their choosing. Though Fletcher, Payne, and Gleaves and their children were now free, all three women faced an unimaginable choice: leave Virginia or return voluntarily to slavery. Since the three failed to choose a new master, they were reduced to slavery because they had remained in Virginia for more than twelve months. So the women returned to the home of Alfred Rector. Here, they were under the charge of “Grandma Kitty” (Ayres’s mother) and Alfred’s daughter, Ann Rector (half-sister of Ayres).

For the purposes of this article, the focus narrows in on one of those three slaves — Mary Fletcher and her children fathered by Ayres: Viana (born 1850), Sallie (born circa 1852), and Fannie (born 1858).

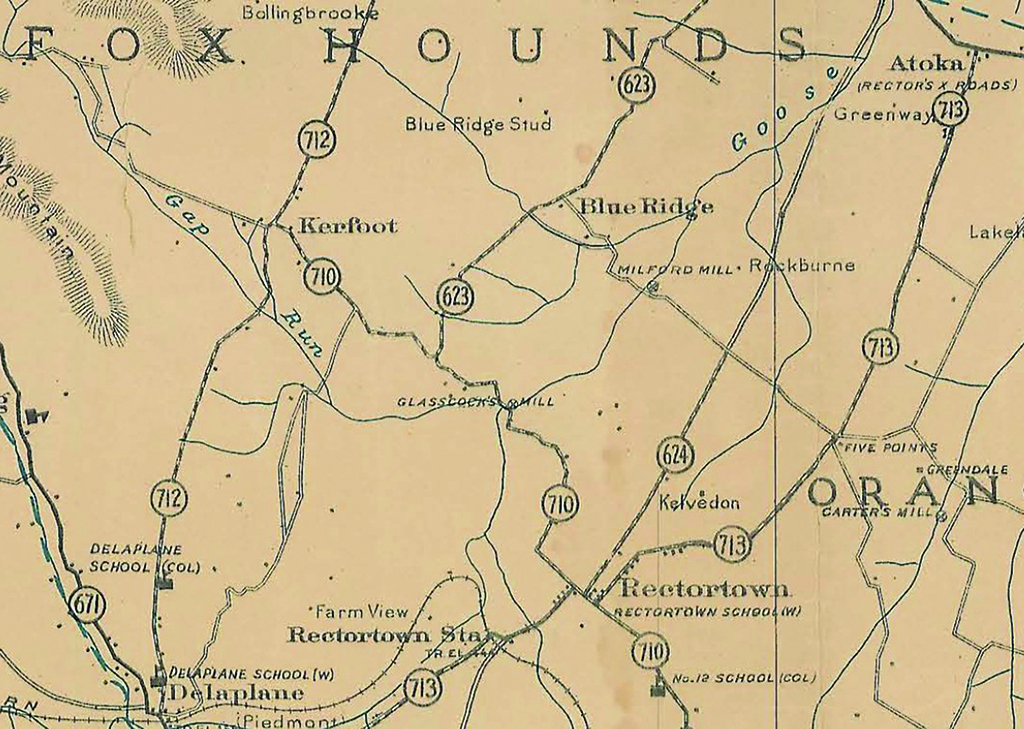

1934 map of Rectortown shows Rt. 713 (Maidstone Rd.), Rt. 710 (Rectortown Rd.), and Rt. 624 (Lost Corner Rd.). Photo courtesy of Fauquier Heritage and Preservation.

In Mary Fletcher’s petition filed with the Fauquier County Circuit Court on Sept. 5, 1860, she describes the reason for her choice to stay: “That she is married and her husband is a slave who could not accompany her. That she has several children, besides those provided for by the will of her late master [Charles Rufus Ayres], all of whom are young and helpless, and that if she goes away, she parts from all whom she has ever known, and goes a friendless stranger, to a new state encumbered by helpless children. Your petitioner declares that she deliberately prefers slavery in Virginia to freedom outside of it.”

But Grandma Kitty had other plans for her formerly enslaved grandchildren. She told them to remain until her death — then make their way to Union lines. In August 1862, she died, and after her burial, escape plans were underway.

Led by a slave known as Uncle Ben — Ayres’s former personal body servant — the group of escapees walked east toward Fairfax County and Union lines. Narrowly escaping danger, they took turns carrying little Fannie and the other younger children. Keeping off roads for fear they would be captured by rebels, they trekked through woods, dreading wild hogs that freely roamed the forests for food, according to the Fare Facs article.

After walking about “forty-two miles” from Rectortown passing through Fairfax Court House (today, Fairfax City), they arrived at Fort Williams, a Union army fortification west of Alexandria, Virginia. But the route was much longer since they had to avoid roads, Confederate cavalry, and enemy pickets. After traveling for two days and nights they arrived at Fort Williams, as Uncle Ben would later state, “mostly dead and starved.”

Now behind Union lines, the story turns. Just before Christmas 1862, Viana (age 12), Sallie (age 10), and Fannie (age 4) met a woman named Catherine S. Lawrence. She was from New York and worked as a Union Army nurse in the Convalescent Hospital at the Episcopal Seminary (currently, Virginia Theological Seminary) in Alexandria. During the Civil War, it housed 1,700 wounded Union troops.

One day, she “happened to see several white girls amongst a group of freed slaves,” the Fare Facs article states. Lawrence described the smallest child (Fannie): “The little girl had flaxen hair and dark blue eyes, but dark complexion, or terribly sunburned.” Basically, she was shocked to learn that the three girls were actually light-skinned slaves. Unmarried and a staunch abolitionist, Lawrence chose to adopt all three. But eventually, Viana and Sallie were sent to live with families in New York while Fannie remained with Lawrence. At the age of 15, Sallie died on Oct. 21, 1867. Four years later, Viana died at age 21, circa 1871.

In a sworn deposition taken on Oct. 9, 1871, Fannie was asked what became of her sisters after they entered Union lines. She answered: “They came North with Miss Catherine S. Lawrence and myself; Viana lived with John A. Rumsey in his family at Seneca Falls N.Y. until 1867, when she went to live with Dr. Dio [Diocletian] Lewis. Sally lived with Dr. ‘Dio’ Lewis from the time she came North until she died [Oct. 21, 1867] at Lexington Mass. at his house. I was at said Lewis’ house with Miss Lawrence a short time before Sally’s death and saw her there.”

Fannie with her adoptive mother, Catherine S. Lawrence, May 1863. Photo by Library of Congress.

And Fannie? She would go down in history as the most photographed slave child in history. Her popularity started on May 10, 1863 at the age of five when she was baptized by evangelical abolitionist, Rev. Henry Ward Beecher (brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, known worldwide for her abolitionist novel, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” published 1852). The baptism took place in Beecher’s Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, New York; she was baptized as Fannie (for her birth name) Virginia (for place of birth) Casseopia (for mythological Greek queen of unrivaled beauty) Lawrence (surname of her adoptive mother).

But before baptizing her, Beecher held her up to his congregation, declaring, “This child was born a slave, and is redeemed from slavery!” An audible gasp could be heard from the shocked parishioners who assumed the child to be white.

“A benevolent woman [referring to Lawrence] who was nursing our sick soldiers in the hospital at Fairfax, found her, sore and tattered and unclean,” Beecher said. “The whole force of my manhood revolts and rises up in enmity against an institution that cruelly exposes such children to be sold like cattle.” He was interrupted by spontaneous applause. He concluded, repeating, “Look upon this child, and take away with you the impression of her beauty, and remember to what a shocking fate slavery would bring her! May God strike for our armies and the right, that this accursed thing may be utterly destroyed.” This followed with renewed applause.

After her baptism, Rev. Beecher arranged to have Fannie photographed; in fact, she posed at least 17 different times, often with her adoptive mother, Catherine S. Lawrence. Basically, little Fannie was “exploited from the pulpit, and later with her image, as propaganda to further his abolitionist aims,” the Fare Facs article states.

Fannie Virginia Casseopia Lawrence at age five in 1863. Photo by Library of Congress.

It worked. Little Fannie’s “carte de visite” photographs were widely popular in the north making her the “most photographed slave child in history,” the article claims. It was at this point that her career as a “redeemed slave child” began, funding the abolitionist movement and assisting with education expenses for freed slaves. The reasoning was that people might be more sympathetic to support the cause if one could imagine that child in the photographs was one of their own.

After Viana’s death in 1871, Fannie attended school and grew into a woman. But like her sisters, her life, too, did not end well. The Fare Facs article states Lawrence’s sentiments: “The little one that I adopted and educated, married one whom I opposed, knowing his reckless life rendered him wholly unfit for one like her. When sick and among strangers, he deserted her and an infant daughter and eloped with a woman, who left her husband and two small children. My three Southern children are all laid away, for which I thank my heavenly Father.” Fannie’s death date is unknown, but she is believed to have died sometime before 1895. Her burial site is also unknown but is believed to be in New York.

And Catherine? In 1873 at the age of 54, she lost her home in the village of Mexico, New York, for nonpayment of a debt. Two years later in 1875, she applied for and received a pension for her service as a Civil War nurse. She also relied on the charity of friends. In 1893 at the age of 74, she published her autobiography, “Sketch of Life and Labors of Miss Catherine S. Lawrence Who in Early Life Distinguished Herself as a Bitter Opponent of Slavery and Intemperance.” The book’s primary focus was about her life as a Union Army nurse and the adoption of Viana, Sallie, and Fannie. At the age of 85 in 1904, she died, destitute, in Albany, New York. She is interred in the Old Stone Fort Cemetery in Schoharie, her birthplace in New York.

The murder of Charles Rufus Ayres over a farm gate swung wide open a domino reaction of change. What started out as an argument — ended in freedom for slaves. As they say, when one door closes, others open. ML

Published in the February 2021 issue of Middleburg Life.