Seeking National Register Designation for Willisville

By Heidi Baumstark

Recognition. That’s what the tucked-away hamlet of Willisville—about eight miles west of Middleburg—may soon receive.

The Mosby Heritage Area Association (MHAA), an historic preservation and conservation nonprofit in nearby Atoka, has teamed up with the Willisville community to get this well-preserved village official recognition on the National Register of Historic Places for its historical significance and the tenacity of a handful of formerly enslaved men and women who established the community in the 1800s.

The hope is to add the 24-acre Willisville Historic District with its 16 structures many of which sit along the narrow graveled Welbourne Road to the National Register.

Dating to the Reconstruction era (1865-1877), the village was founded when formerly enslaved African Americans from the neighborhood purchased land from adjacent landowners. Some landowners helped them establish the neighborhood school and church, two essentials for any community.

According to records, the original log Willisville School house was built around 1868 and served as a combination school/church. Fire destroyed the structure in 1918. Built in 1919, the second school building is currently a residence.

The old stone Willisville Chapel which is still used for worship services was built in 1924. The old store which served the community for years is today a residence.

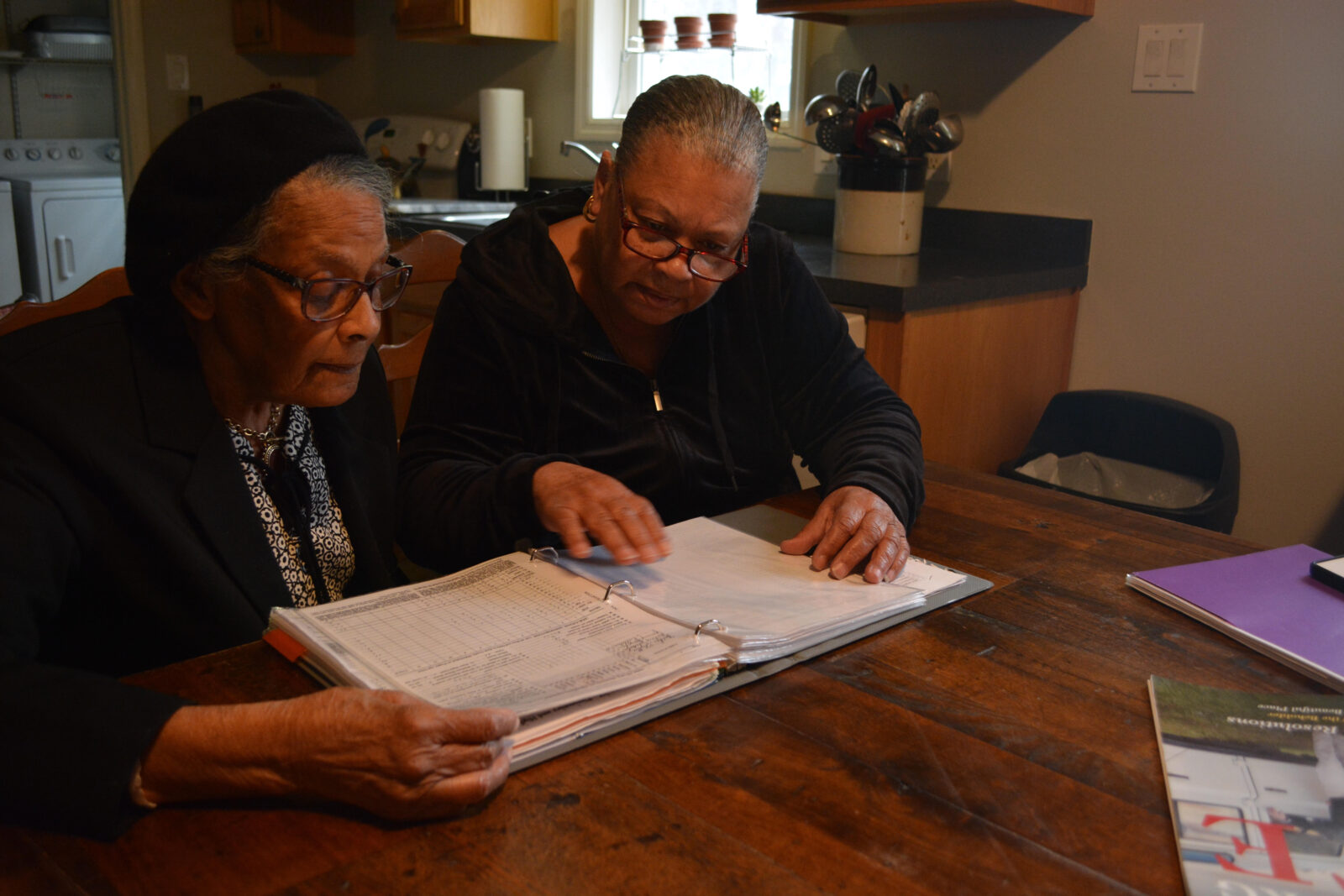

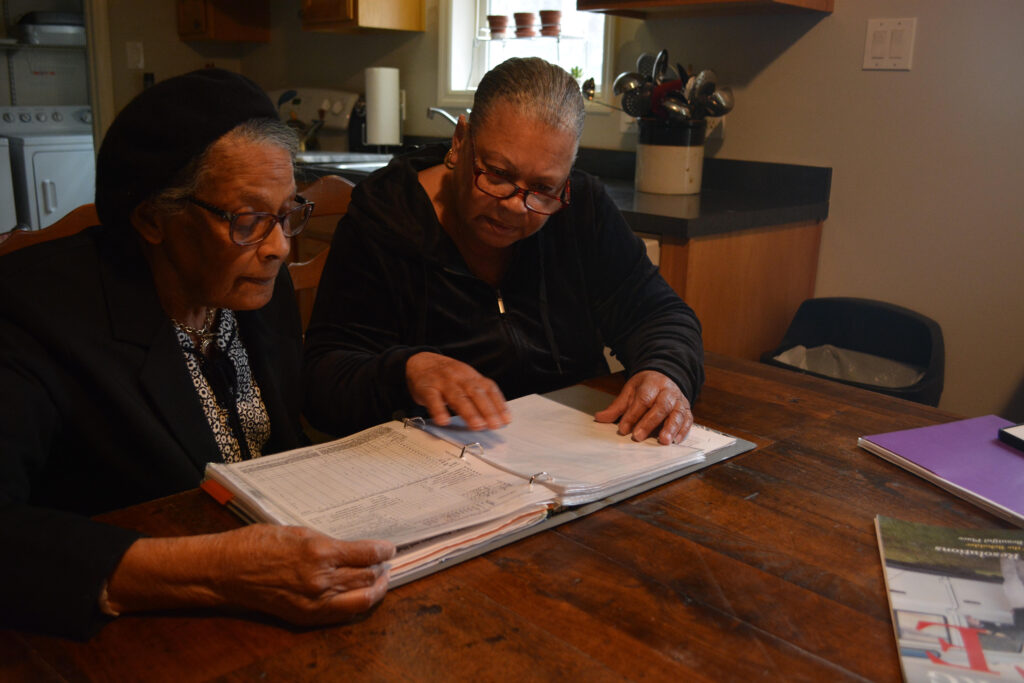

Spearheading the effort to get Willisville listed on the National Register is long-time resident Carol Lee who grew up in Willisville. She became interested in researching the village beginning with her own family. “My family has been here since 1935 when my mother, Anne [Brooks] Lee, 91, moved here with her parents (my grandparents) when she was a little kid,” Carol explained. “My family has lived in the same house on Welbourne Road since 1935—for 84 years. I grew up here, moved away, and came back over 20 years ago. Now I live next door to my mom.”

“Before moving to Willisville, we lived down the road at Welbourne. That’s where my father worked,” said Anne Lee.

MHAA board member Dulany Morison is heading up the formal National Register application process whose family’s nearby 565-acre estate, Welbourne, has been in the area since the late 18th century. Welbourne (circa 1770) is the home of Loudoun native Colonel Richard Henry Dulany (1820-1906) who rose to the rank of Colonel in the Confederate Army during the Civil War and is the great, great, great grandfather of Morison. An historical marker on Route 50 near Atoka states that Welbourne, a late 18th century stone farmhouse, evolved into an “imposing mansion and was the home of Col. Richard H. Dulany, C.S.A. … Visitors during the Civil War included Stuart and Mosby.” Colonel Dulany is also credited as the founder of the Upperville Colt and Horse Show in 1853. Today, it is known as America’s oldest horse show.

Considering its objectives at the beginning of 2018, MHAA was interested in highlighting the region’s African American villages, and the Lee family history spans four generations. “We wanted to give Willisville recognition. Anne Lee is a long-time friend and I reached out to see if she was interested. She asked her daughter, Carol, who was thrilled since she had been studying the area,” Morison explained.

“In 2015, my cousin and I started researching our family roots and then every house in the village. My mother introduced me to Dulany [Morison]. We started talking about the possibility of Willisville on the National Register of Historic Places,” said the younger Lee.

Morison said they put their heads together and Carol had the idea of a gospel concert last August as a fundraiser. “Our role was to promote, facilitate, and help Carol rally the community to the cause and be a resource to make this happen,” said Morison. The August 2018 concert at Buchanan Hall in Upperville featured The Gospel Tones, Mt. Olive Baptist Church in Rectortown; The Voice, Agape United Methodist Church in Purcellville; and Sistah of Praise, Middleburg.

The concert proved to be a resounding success. About 300 guests attended and enough funds were raised to allow MHAA to hire Jane Covington, an architectural conservator by training and a local historical preservationist. Covington’s job includes researching the village, preparing and submitting the detailed application by this summer to the Virginia Department of Historic Resources. After a lengthy board review, the application will go for nomination to the National Register of Historic Places.

“There’s so much history here. Not only are the houses unique, but the families who make up the village are remarkable. Many have been here for generations. A roadside marker would be very appropriate here. If the village would like a marker, they can make that happen,” said Jane Covington. If accepted on the National Register, the listing does not restrict benefits or land use, but does confer honorary designation, recognizing the village’s historical significance.

It is not exactly clear how Willisville got its name, but some believe that it’s inferred that the village was named after Henson (also seen in records as Heuson, Hasen, or Hughes) Willis, and his wife, Lucinda. According to Carol’s research of death certificates, Henson Willis was born 1836 and died June 20, 1873 at the age of 37. Lucinda Willis was born 1830 and died in New York on Nov. 11, 1920 at the age of 90. They had five children. Henson is buried with his son, Hanson Willis, in what some call the old Willisville cemetery near the old school, which has 32 graves. Hanson’s tombstone reads “Hanson Willis 1862-1900.” A smaller weathered tombstone that only bears the letter “H” and “W” (with other illegible lettering) is presumably Henson’s. Lucinda is buried in New York.

Research shows that the pre-Civil War Willis House dates to 1840 or 1850 and all of the early residents were local to this area. Land tax records show that at the beginning of the Civil War about 100 African Americans were living free in the Mercer District in southwest Loudoun. Of those, only five were listed as landowners highlighting the rarity of land ownership. Free blacks mostly resided as tenants on property owned by white farmers. Covington said Henson was living free, likely as a tenant at the edge of Townsend L. Seaton’s Catesby, a farm at the south edge of Willisville. At that time, the area was known as “nr [near] Clifton” since Clifton Mill was nearby. Records were poorly kept, but Henson was a “mechanic,” according to his death certificate, possibly working at Catesby or Clifton Mill, thereby allowing him the possibility of earning an income to support his freedom and his family.

Much of Willisville’s history is recorded in Loudoun Discovered Communities, Corners & Crossroads, Volume III, The Hunt Country and Middleburg, by Eugene M. Scheel, local historian and mapmaker of Waterford, Virginia. His book has an entire chapter on Willisville where he states that “Heuson” and his wife, Lucinda Willis, had possibly been owned by Seaton of Catesby, which is the site of the 1862 Battle of Unison. Lucinda was owned by Ida Dulany who lived at nearby Oakley near Upperville. Covington’s research shows that Lucinda appears in Ida’s diary she kept during the Civil War. According to Loudoun County’s Record of Free Negroes (1844-1865), Henson was freed by William Carr, but the relationship between Henson and Seaton is unclear.

After the Civil War ended in 1865, white landowners sold or deeded part of their property to freed slaves. Covington added, “These landowners still needed a labor force nearby and everyone was in walking distance, so it made sense to have them close by.” So a village sprung up.

Freedmen’s Bureau records show that in 1868 Colonel Dulany of Welbourne wrote to Lieutenant Sidney B. Smith of the Freedmen’s Bureau in Middleburg asking for a school. He wrote, a “large number of colored people in his neighborhood have requested him to apply for assistance to build a school house …” Dulany was allotted $150 from the Freedmen’s Bureau and the community raised $40 to go toward the purchase of a half-acre of land from John Armistead Carter (1808-1890) of Crednal Farm. Carter was a Virginia lawyer, farmer, and politician who represented Loudoun County in the Virginia General Assembly both before and after the Civil War. The earliest deed in Willisville dates to Oct. 1, 1868 for the formation of this school, which was built of logs measuring 18 by 30 feet at the western edge of Carter’s farm. Carter sold his land to three former slaves George Evans, (possibly enslaved by the Carter family), Garner Peters (enslaved by the Dulany family), and Benjamin Berry for a combination school/church “for the exclusive use and benefit of young colored persons for a school house [also] used on Sabbath days for holding Sunday school,” Scheel writes.

Between 1872 and 1876, Carter of Crednal and Seaton of Catesby sold six additional lots along the western edges of their farms to formerly enslaved and freemen, including John Howard, Lucinda Willis, Sarah Jackson, and George Evans. This enclave of homes would later become known as Willisville. Carol confirmed that the north side of Welbourne Road (where the school, old cemetery, and church are) was land owned by the Carters of Crednal while the south side of the road (where most of the houses are, including what was the old store) was land owned by the Seatons of Catesby.

On Nov. 7, 1874, Seaton and his wife, Mary, deeded three acres of their property to Lucinda Willis for $100. Carol said, “Lucinda purchased the three acres from Seaton; Henson had died the year before.” The Willis house still stands, but is much enlarged. You can still see the old stone foundation and chimney.

On June 1, 1918, the original 19th century school/church burned. In the fall of 1919, a new school was built as a one-room frame structure for $1,200. With the influx of federal funds in 1933, the school was given an additional room in the rear of the building allowing for two sets of grades to be taught at the same time. In 1933, Anna Shorts Gaskins became principal, but well before that, she began her 43-year teaching career there in 1908 when she was just 18. Then, it was just a one-room school and she earned $25 a month. Every day, she began school by reciting “The Lord’s Prayer.” There was always a Thanksgiving and Christmas program along with a Santa Claus.

Anne, born Sept. 3, 1925, remembers attending the school in 1933 when she was six years old, then named Anne Brooks. Official school records for the 1933-34 school year show “Brooks Anne” living “1/2” mile from the school and lists her age as “6” with “Anna Gaskins” as the teacher. Anne remembers, “The teachers were very strict but very good. Grades one through three were in the first room; the back room was grades four through seven.” She also remembers having a “Victory Garden” at the school during World War II. In 1958, the 1919-built school was converted to private use.

The sale of Willisville School was held at public auction on April 4, 1959 on the steps of the Loudoun County Court House. Children were then bused about two miles south to Banneker Elementary School in St. Louis, another African-American village. Anne’s four oldest children attended Willisville, but Carol and her three younger siblings went to Banneker. Carol said, “You got your learning and were taught to read and write. I remember going to Banneker in seventh grade; it wasn’t integrated at the time. In eighth grade, we went to Loudoun Valley High School in Purcellville.”

Another important feature in any village is a place of worship. A metal plaque near the church’s front door reads, “Willisville Methodist Church Founded 1869 by George Evans.” Since the existing stone church was built decades later in 1924, church members previously congregated at another location, possibly in homes, and then at the old school/church; but when it burned in 1918, church services were held outside in good weather. During bad weather, services were at Fannie Dulany Lemmon’s cottage at Welbourne.

Courtesy of Michaela Baumstark

According to Scheel’s book, in 1923, Mary (Carter) Dulany Neville offered Willisville churchgoers that if they raised $1,000 toward the construction of a new church she would donate the remainder. Born in Paris, France, Mrs. Neville was an artist and designed the new stone church modeled much like a French country chapel. Churchgoers raised the $1,000 and the site of the church was on Pelham, which had been carved from neighboring farm, Crednal. The total bill for what is now called Willisville Chapel UMC (United Methodist Church) came to $6,500—a record price for an African American church in the Virginia Piedmont.

The church, located at 34008 Welbourne Road, bears the datestone: “Willisville Chapel 1924 June 29.” The younger Lee remembers going to the little stone church as a child; her mother still attends. On a recent walk down Welbourne Road near the church, she pointed out that the steeple is now gone and the bell is out back from the church she once attended. “When they replaced the roof, they didn’t have enough money to put it back,” she said.

Next, comes the old store, which Scheel dates to about 1912. Anne remembers the store and at one time lived in it when it became a residence. It went through a series of owners, but Anne remembers when it was run in the 1950s by Phil McQuay, a St. Louis merchant. Henry Jackson closed the business in the late 1960s. There was once a blacksmith shop near the Welbourne Post Office on Quaker Lane.

Considering the history of Willisville and how the village got its start, Morison added, “It’s a lovely example of a community coming together. Despite everything going on with the times, there was a community that helped each other.” Carol said, “In the south, you heard how blacks really suffered, but you didn’t see it here. These families were allowed to purchase land, to make a community. We had plenty of kids to play with. We had a good life.”

Regarding its significance, Carol pointed out, “I want people to know the village was an area where people could freely settle after the war. Slavery was over. It became a village and it remains a village. People have managed to hang on to their land even with development around. We’ve been able to hold onto our history.”

Being listed on the National Register would acknowledge the 150-year history and give the village a well-deserved recognition of its importance as a surviving community that sprung up during the Reconstruction period. If a marker goes up, it will likely go near the old school at the crossroads of Willisville and Welbourne Roads. And if Willisville gets on the National Register, Morison said, “We’d like to have a wrap-up function to invite guests, donors, and the community to celebrate and educate people more about Willisville. This whole process has been a very rewarding experience.”

Carol said, “Willisville produced some good people. I have no complaints being raised here. Everybody grew up the same way. We were in our own little world. And we were happy.”

MHAA is located in the historic Rector House at 1461 Atoka Road in Marshall, just west of Middleburg. Organized in 1995, MHAA seeks to preserve the unique cultural, historical, and geographical significance of a 1,800-square-mile region of Loudoun, Fauquier, Clarke, Warren, Prince William, and the City of Manassas. Call MHAA at 540-687-6681 or visit their website www.mosbyheritagearea.org for more information and to donate to the Willisville Preservation Project. Or mail donations to MHAA, P.O. Box 1497, Middleburg, VA 20118 with “Willisville” noted on the payment.

This article first appeared in the March 2019 issue of Middleburg Life.