The Inn at Little Washington Celebrates 45 Years of Wins and Whimsy

Written by Beth Rasin | Photos courtesy of The Inn at Little Washington

In the summer of 2020, as restaurants began reopening following the early COVID-19 shutdowns, many meals were a bit muted, with strict restrictions on seating capacities. However, stepping inside the dining room at The Inn at Little Washington, guests experienced the opulent surroundings, the surprising and unpredictable combinations of styles, textures, and patterns on the walls and furniture, and, even more rare in those days, a packed party with every table full.

Full, that is, of mannequins, dressed by a theater company and placed around the tables, drinking wine, eating, holding hands and in one case, even proposing.

“It was our way of enhancing the dining experience instead of diminishing it [during the restrictions],” says Patrick O’Connell, the inn’s proprietor and chef of 45 years. “People were smiling, taking pictures. It was great fun. The intent was to keep the feeling of a party alive.”

For O’Connell, this was just another opportunity for his creativity to set The Inn at Little Washington apart. After all, this was far from the first — or even most daunting — challenge he’d faced while establishing the greater Washington, D.C., area’s first and only three-star Michelin restaurant.

The novel approach garnered 98 media stories worldwide. “The publicity we received by our solution to social distancing allowed us to surge after the pandemic,” O’Connell says.

It’s all part of a resourcefulness he believes is bred into people in rural communities like his adopted Rappahannock County, in the eastern foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. “If D.C. ceased to exist, we’d be fine out here with what we have,” he says, referring to the inn’s farm, gardens, and greenhouse that supply his kitchen — and, he says, the wild raspberries he finds on mid-summer mornings while walking his Dalmation, Luray (adopted from the nearby town of the same name).

“It’s inspirational, and it’s part of the joy of living here,” he says. “You can and will survive; you’re a survivor.”

An Outhouse And A Frying Pan

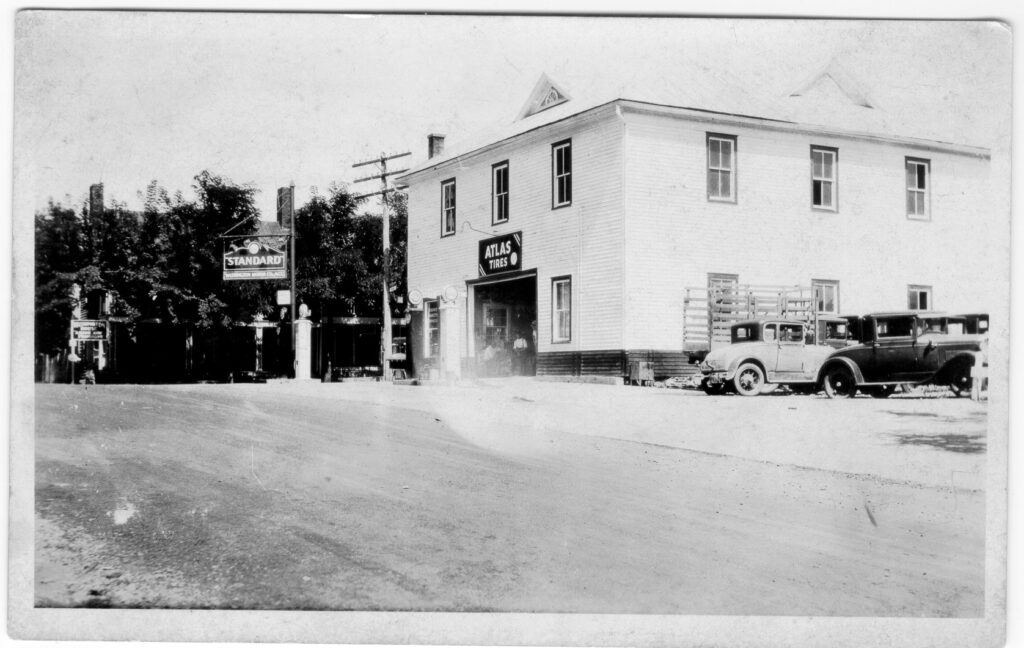

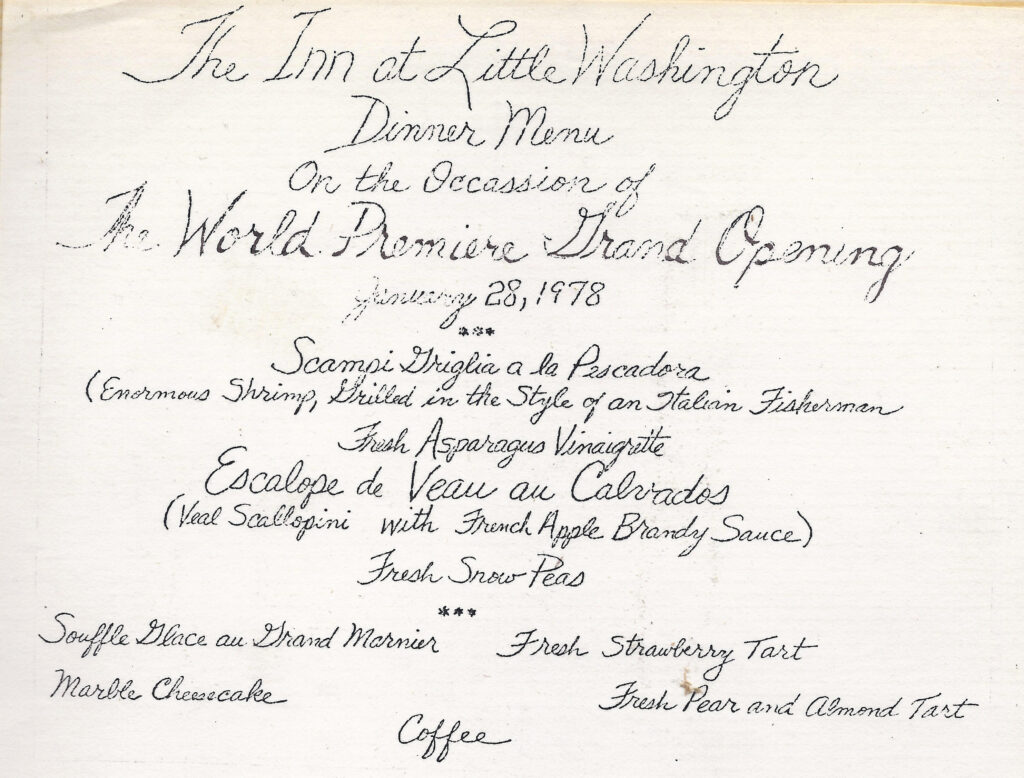

In 1976, O’Connell rented half of a garage that came with a junkyard and outhouse for $200 per month. It was a step up from the mountain shack where he’d started his catering business using a wood stove and electric frying pan. By 1979, he’d purchased the garage that he says had been “patiently waiting for a miracle” and began the journey of creating what would become one of the world’s top restaurants.

“I’ve never been grounded in reality,” he says. “My vision has always been the best of anything.”

But the town, at first, didn’t necessarily embrace that vision. “Change is difficult to adjust to, and it was initially hard to relate to what we were doing,” he says. “People didn’t understand that food could attract people or why it cost so much; they didn’t have a reference point.”

But as the inn took off, earning one award after another, property values soared. With the inn’s contributions via the food and lodging taxes, the town built a sewer and water system. “I think we [now] have a larger fan club than group of mystified people,” says O’Connell, who has continued to buy and improve buildings in the town. In addition to the main inn, five other cottages in the town host guests, and there are shops, gardens, a ballroom, and a walking trail. In late 2021, O’Connell added another, more casual, dining option with Patty O’s Cafe & Bakery, which, like the inn, also occupies a converted garage.

The process of gaining trust and growth took time. But his most recent expansion plans, which include a carriage house with 10 rooms, a courtyard, pool, and spa, unanimously passed the town council.

O’Connell believes establishing the inn in Rappahannock County made the endeavor twice as difficult as it would have been if done close to a metro area. “Things move more slowly; there’s fear of change. There was no liquor license when we moved here, to a town with a population of 100,” he says. “Initially there was nothing delivered here, and it was considered impossible. We didn’t even have the electric to run AC or the kitchen. They were hurdles we had to overcome. It wasn’t just considered a challenge; it was considered insurmountable.”

But O’Connell says his stubbornness, maybe even a little insanity, drove him on.

“It’s like living in a film; something happens every half-hour that I find funny or whacked, just the unlikeliness of what has happened here,” he shares. “No one knows what makes it tick, where it’s come from to what it is now, especially people in our industry. It’s a kind of tenacity, like a plant that thrives in the desert — a beautiful flower that’s not watered, in parched soil,” he adds with a laugh. “I have a sense that it’s come full circle, that it’s now almost making sense.”

Inventiveness And Whimsy

In the early days, while running a catering business, O’Connell says he could briefly rest following an event. Now, however, he rarely takes a break. “You get in a groove, and it’s like breathing; you don’t stop. There’s always something pushing you forward and pulling you back, swimming against the tide,” he says.

But he doesn’t think of it as work. Instead, “It’s like a big house with lots of company,” he says.

After the restaurant’s first year, he used the money he’d earned to fly to France to better understand the benchmark for the world’s finest dining. “There was not a model in the U.S. for what we wanted to do,” he explains. “The culture there has a different respect for chefs. They’re regarded as movie stars, celebrities. None of that had reached America then.”

He especially fell in love with Michelin three-star properties in the countryside. “You’d see them in these tiny towns, where people flew in by helicopter, heads of state and royalty. Most of them were in their third generation of operation, because it takes that time to build the place and clientele.”

Even as he learned about his international competition, O’Connell wanted more for his establishment.

“The quality, inventiveness, and whimsy in the food is the lure that draws people in,” he says. “But it’s the attention to detail that they remark on every night. Every aspect of the experience is at the same level — the room, breakfast, tea, dinner, the gardens, all are one.”

He likens the experience to visiting a private home in the 1920s, with an enormous staff, anything provided or accommodated, and completely separated from reality.

In addition to transporting people out of the modern, urban environment, he also wants to remove them from the culture of sameness and commercialism and imbue a sense of place.

“People should clearly feel where they are,” says O’Connell, who believes the focus on locally grown ingredients is one of the reasons they earned the Michelin Guide’s Green Star sustainability emblem. “They’re not in the city, and the menu should reflect that.”

As he toured top European restaurants, however, O’Connell noted one thing he didn’t want to emulate: the intimidating atmosphere. “For myself to thoroughly enjoy a meal, I had to be myself, relaxed,” he says. “I think this is the greatest contribution American chefs have brought to fine dining: the relaxed approach, the idea that it can be fun. We take our work seriously, but we don’t take ourselves seriously. We have fun. This is more like going to a party at someone’s house. You can be whoever you are, come as you are. There’s no dress code, expectation of the guests or intimidation. If you’re not having fun, we feel like we haven’t succeeded.”

An Inspiration

Even before encountering the challenges presented by a small, rural town, 30 or 40 minutes from the nearest grocery store, O’Connell had to surmount an American culture in which, he says, restaurant work was not highly regarded. Yet from his first job with food, he immediately knew it would be his home.

“It was a group of diverse, fascinating people,” he says. “It encapsulated all my interests: theater, food, people. It was where I belonged.”

Decades later, one of his proudest honors of countless national and international awards is his National Humanities Medal, received at the White House in November 2020.

“This was not just for myself but recognition that chefs would be regarded like other artists,” he says. “It was very meaningful that the culture recognized important chefs and great restaurants.”

Now, he says, the onslaught of food television, among other factors, has made the idea of being a chef seem glamorous, artful, prestigious. “It’s a false sense of reality, but it’s intrigued [people],” he says.

Still, O’Connell, 77, a James Beard Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award winner, believes he’s only achieved about 60 percent of his vision. “We still have the 50th anniversary to look forward to,” he says. “Every five years this place won’t resemble itself.”

He has no plans to retire, claiming he “doesn’t like golf or staring at the ocean.”

“No one should retire from welcoming guests to their home,” he says. “I’m doing what I enjoy.”

And it seems that the challenges he’s overcome, whether related to infrastructure, supply chain, or a global pandemic, have somehow added to his pride — and influence.

“This place has inspired many people, that you can fulfill your dream in an out-of-the-way place, not through the conventional method in a city,” he says. “You can do it your way. You don’t have to be in New York to succeed. I hope I’ve given them a sense of reverence, passion for what I’m doing. If you keep doing it long enough, if you stay the course, good things will come your way, if you’re lucky.” ML

Published in the August 2023 issue of Middleburg Life.