Then & There: A Valentine’s story

Photos and story by Richard Hooper

“How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.”

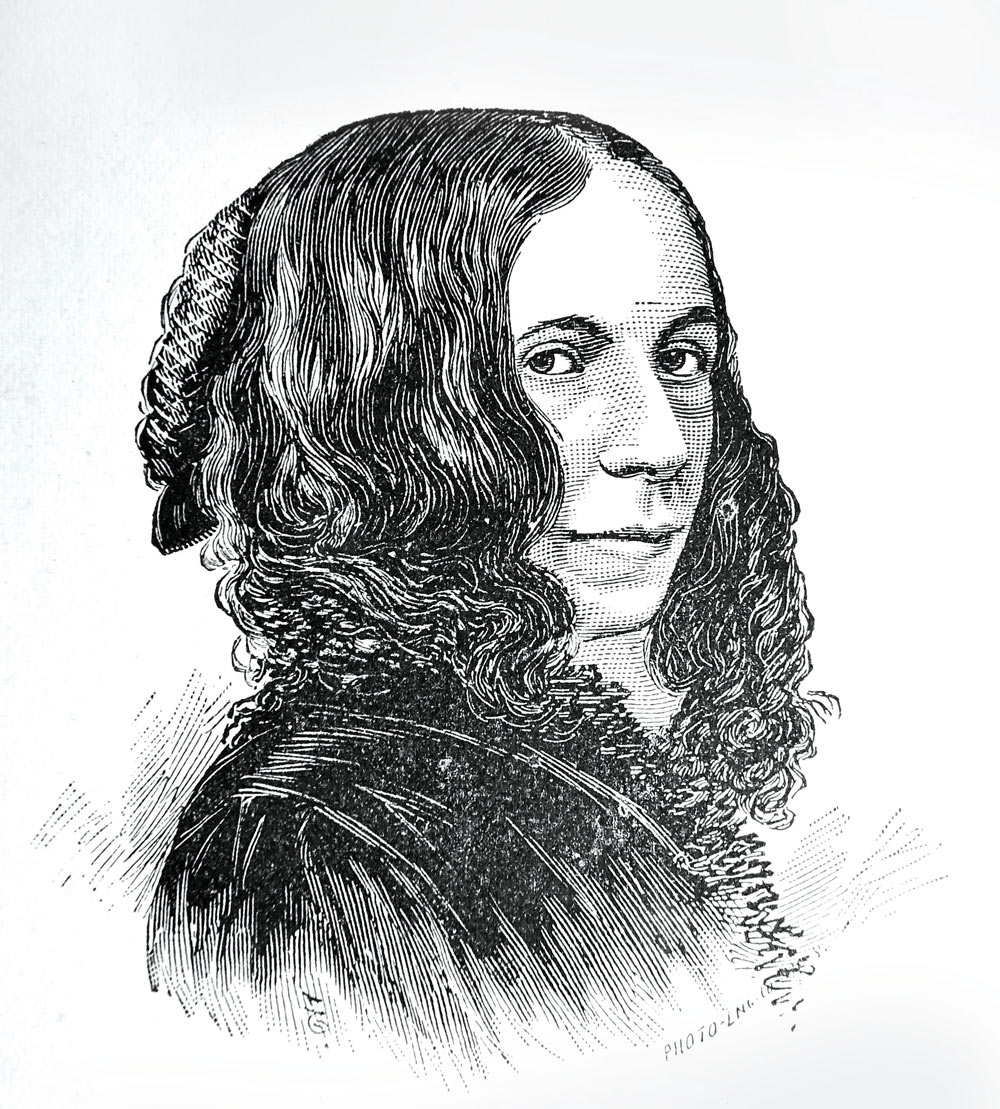

Thus begins one of the most well-known love poems in the English language, secretly composed by Elizabeth Barrett while making the acquaintance of, and being courted by, Robert Browning.

In 1841, having spent the last two years in Torquay attempting a recovery from a variety of indefinite illnesses which had plagued her since mid-teens, Elizabeth rejoined her family at their residence at 50 Wimpole St. in London. She was 35 years of age, an invalid confined for the most part to her room, taking most of her meals there alone, as well. Writing was her main activity and even that, her doctors advised, was too strenuous for her.

Nearly four years later, she praised the poetry of Robert Browning in one of her works. He responded to her on Jan. 10, 1845, in a long letter praising her work in return. Elizabeth replied her thanks, further expanding her praise of Robert’s writing. They both revealed bits about themselves within their effusions about the other in letters that were open and straightforward. Yet one can feel warm embers waiting to be fanned.

“When you came, you never went away. I mean I had a sense of your presence constantly.”

-Elizabeth Barrett, in a letter to Robert Browning

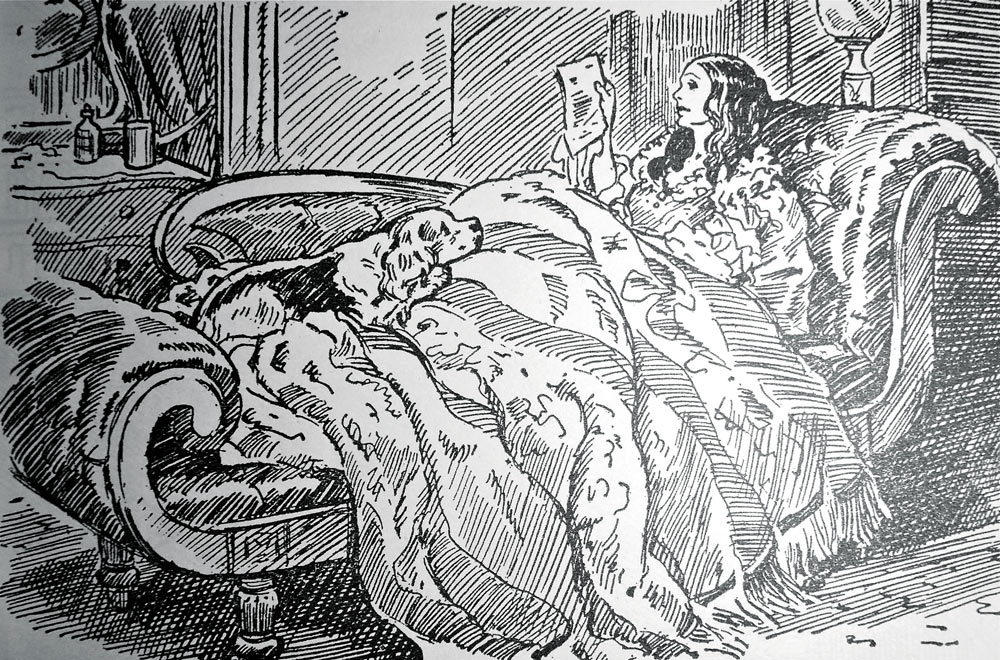

Due to her health, Elizabeth allowed very few visitors. But four months after their letters began, she allowed Robert to visit. She received him on her sofa in her third-floor bedroom, her usual station for receiving the infrequent guest. He stayed an hour and a half. The next morning Elizabeth confided to her father that she had been overwhelmed by his presence.

In a letter to Robert, she wrote, “When you came, you never went away. I mean I had a sense of your presence constantly.” She was smitten, but did not know quite what that was. Her poetry, a few friends, her family and Flush, her cocker spaniel and constant companion, were her salvation and joy. She dared not think of a future outside of her room. Describing the jolt that Robert gave her, she wrote in her first love sonnet:

…a mystic Shape did move

behind me, and drew me

backward by the hair,

And a voice said in mastery

while I strove, …

“Guess now who holds thee?”

_____ “Death,” I said. But there,

The silver answer rang…

“Not Death, but Love.”

Elizabeth later asked Robert for the letter back but he had destroyed it. It is the only letter missing from their voluminous correspondence.

Had Robert proposed marriage? That was something Elizabeth had not entertained. While she may have been shocked, she certainly did not want the exciting friendship with Robert to die. She also feared that Robert was of such a disposition as to fall in love with anyone, and that eventually she would only disappoint him.

On Robert’s visits to Elizabeth, he brought bouquets of flowers to adorn her room. The visits were kept semi-secret from Elizabeth’s father. An autocratic man, Mr. Barrett strongly preferred that his children not marry and remain within the household – except, of course, when a son was dispatched to Jamaica to tend the family plantation.

During Robert’s visits, Elizabeth began writing the sonnets, for which she would become so famous. The 43 poems describe the course of her feeling unworthy of Robert’s love and evolve from tentative to full recognition of her love for him. Such delights are described as Robert’s first three kisses and exchanging locks of hair. Lest one think her verse is burdened by Victorian morays, she debunks that notion in the 10th sonnet writing, “And love is fire; and when I say at need / I love thee . . mark! . . I love thee!”

As the winter of 1845 approached, Elizabeth’s doctor recommended that she go to Italy for the season. Mr. Barrett, however, would not give his consent. Robert had planned to join her there, but now all they had was another bleak winter with weekly visits ahead of them. The disappointment was unbearable. Elizabeth began to think that her father viewed her as chattel and realized that her only path to a full life was with Robert.

With many reservations, Robert and Elizabeth began to plot their marriage. Knowing that Elizabeth’s father would never grant consent, they thought perhaps he would accept it after the fact. The plotting went on until circumstances necessitated abrupt action. On Sept. 12, 1846, Elizabeth, accompanied by Wilson, her maid, slipped out of the house and began the walk to St. Marylebone Parish Church. On the way, Elizabeth nearly passed out. Wilson had to procure smelling salts for her and then a cab. Making it to the church, she met an anxious Robert.

Now married, Elizabeth returned to Wimpole Street and hid the event from her family for another week. She had already secreted her luggage from the house, when she and Wilson, this time accompanied by Flush, sneaked out of the house to meet Robert and cross the English Channel to find a new home in Pisa.

She left behind letters of explanation, and took with her the love sonnets she had written. It wasn’t until 1849 that she showed them to Robert. When published the following year, they were entitled “Sonnets from the Portuguese.” The title was a private reference to a term of endearment that Robert used for Elizabeth. He would sometimes call her “my little Portuguese.”

Happy Valentine’s. May your love be as strong. ML

[Next Month – Flush’s Story]

(Richard Hooper is an antiquarian book expert in Middleburg. He is also the creator of Chateaux de la Pooch, elegantly appointed furniture for dogs and home. He can be contacted at [email protected].)