Then & There: Hockey on Horseback – The Early Years of Polo in England

By Richard Hooper

Under the heading of HOCKEY, a correspondent to the April 16, 1870, issue of “The Field,” a weekly English journal that billed itself as “The Country Gentleman’s Newspaper,” endeavored to explain the game of polo (or, as he called it, “hockey on horseback”) as he played it while stationed in India.

To begin play, the ball was tossed onto the ground between the opposing teams lined up about 100 feet apart, who would then charge toward it like two opposing cavalries about to clash. Other than the opening of play, his description of driving the ball up and down the field could likewise describe polo of today. In the region of India where he played, the game was called “kunjai” and the field was about 50-by- 120 yards. He provided a sketch of a “kunjai” stick, which looked much like today’s polo mallet, but with a smaller diameter head. From his description, it seemed like there were six or seven players per side.

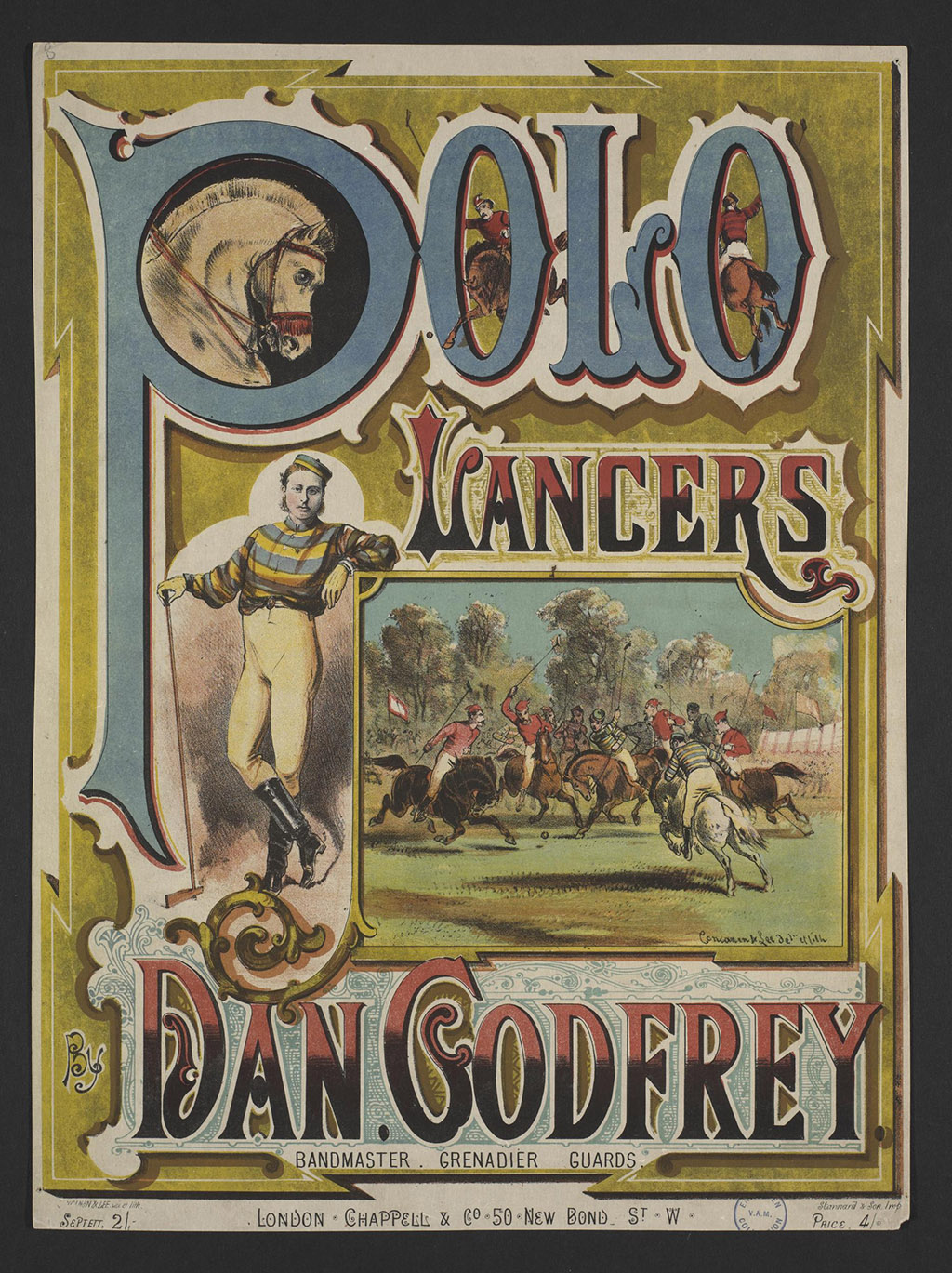

Sheet music cover for “Polo Lancers.” Photo Courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

In the same issue, another contributor stated that where he played in India, the game was called “chogun bazi.” His field was about 400 yards long by about 120 yards, but it was barrel-shaped, appearing wider at the middle and narrower at the ends. Neither writer mentioned what constituted the length of a match.

Several months later, another correspondent added his experience. The size of the field, he thought, simply depended upon the available level ground. In one town, the game was played on the main street, with throngs of players on both sides. He recommended, though, that the field be 300 to 350 yards long by 150 to 200 yards wide (fairly close to today’s standards) and barrel-shaped.

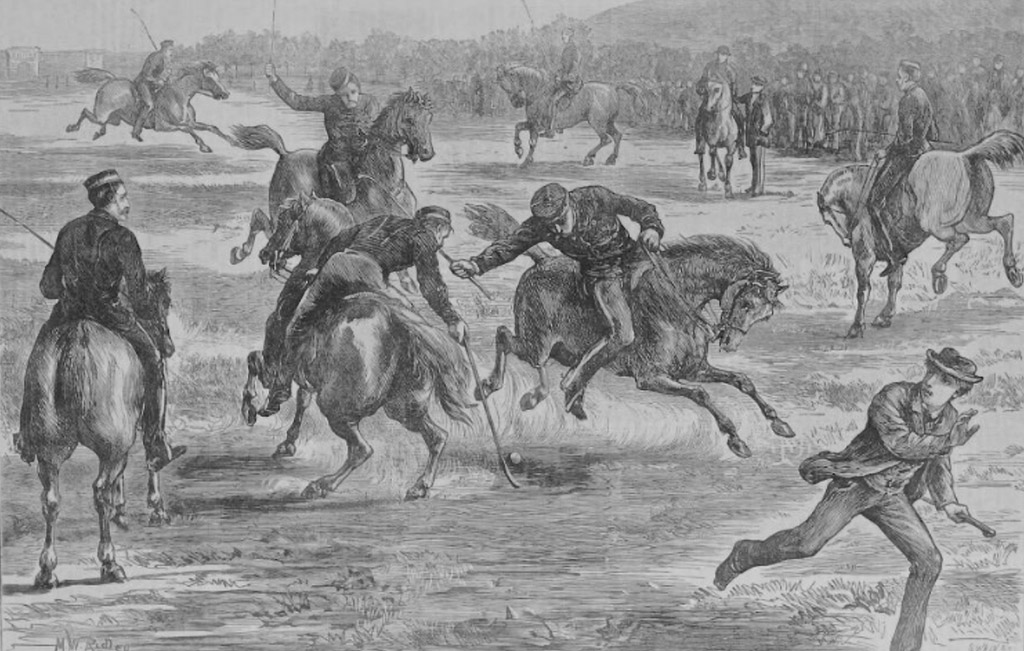

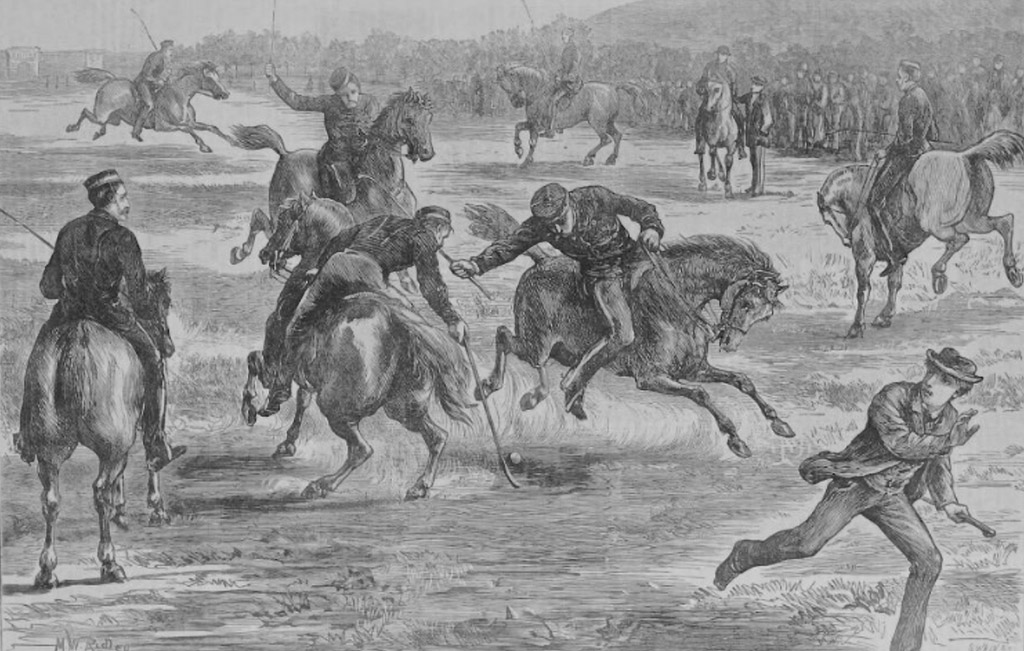

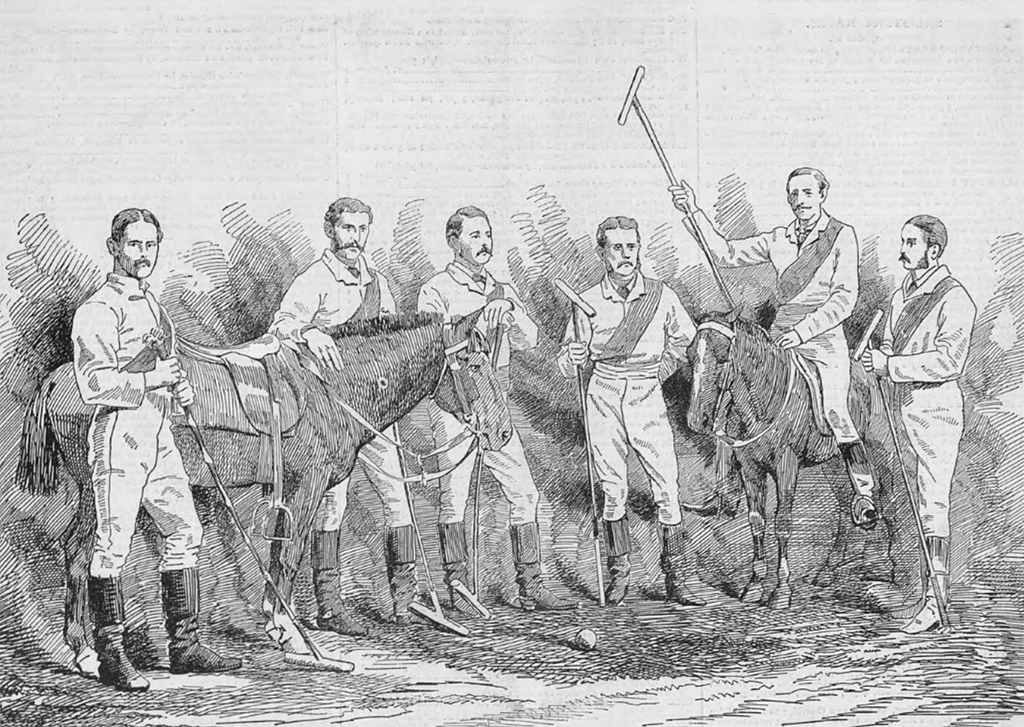

English polo in 1872. The mallets used in this match were hockey sticks.

Methods of play varied from region to region and he described two ways to begin play. In both, the players are lined up front to back (not side by side as previously described), with the front players from 50 to 100 yards apart. In one version, the ball was given to a player of the team that had won the equivalent of a coin toss. That player carried the ball in his hand while riding forward at “fair speed.” Before reaching mid-field, he tossed

t into the air and, while aloft, hit it with his mallet to begin play. As this method “requires some skill,” the writer preferred the second, whereby the ball was placed in the center of the field and a player from each side galloped toward it, trying to reach it first and knock it away to his team’s advantage.

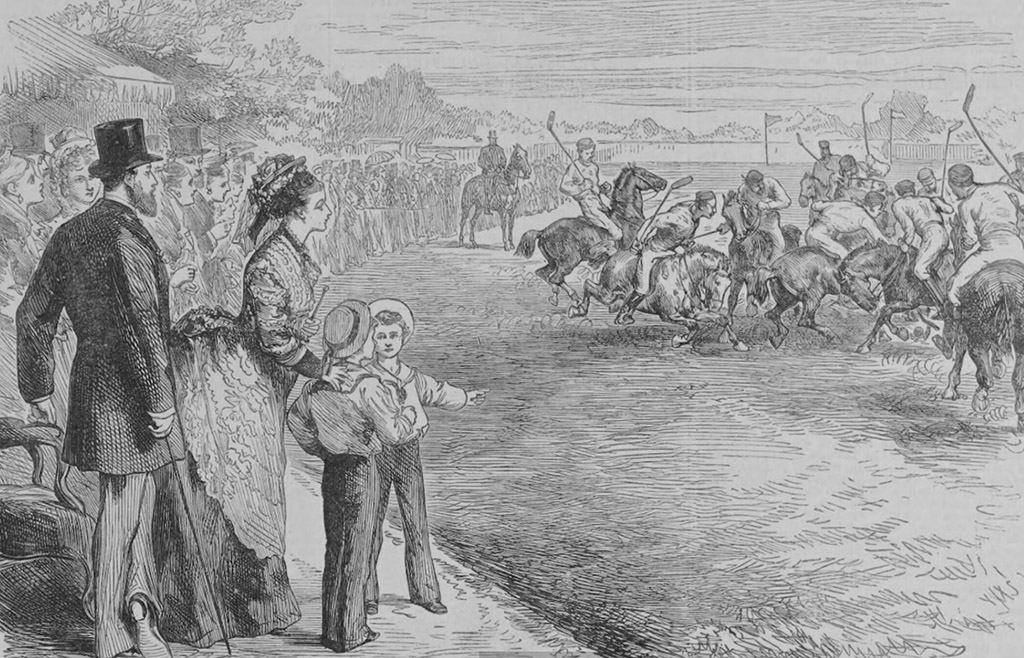

Polo at the Hurlingham Club in 1875, with the Prince and Princess of Wales. The mallets are shaped like golf clubs.

The writer, who had been secretary of the Peshawar Polo Club in 1868, provided a few of his club’s rules and added other observations. After describing one form of hooking, during which the head of the stick became entangled in his opponent’s reins after “nearly putting out the rider’s eye,” stated that the practice was “rather irritating, and should therefore be forbidden.” As to sticks, the head of the mallet could be made from a piece of old cricket bat about 6 inches long with a hole bored into it to admit the shaft. “The number of player’s may be unlimited,” but if four or fewer, each player should have two ponies. He thought six players per side was the best number, as it tired the ponies less (if more than that, they got in each other’s way) and that 13 ½ hands was a bit tall for a “hockey pony.”

The Peshawar Club secretary offered an additional tip. Because the game was played in hot weather, “a supply of brandy and soda-water will be found not only very grateful and refreshing, but most necessary …”

The term “hockey on horseback” was used for a number of years, gradually losing out to “polo,” which originated with “pulu,” the word that Tibetans used for the game. By 1872, after being introduced in England a few years prior, the game was gaining momentum, with formal matches played at locations scattered around the country.

The English team at Calcutta in 1876 for the Prince of Wales’ visit. The mallets look much more like mallets of today.

Windsor Great Park had already been the site for several matches prior to one there on July 16, 1872, that accelerated the popularity of the game. The match was between the Royal Horse Guard and the 9th Lancers, who had been active in spearheading the promotion of the game. Three tents had been set up to serve luncheon for hundreds of the royalty, nobility, and aristocracy, highlighted by the Prince and Princess of Wales. Their presence propelled the game into respectability. It would soon become fashionable. On this occasion, there were six players per side, but no report as to the length of the field. Previous matches, though, had been played on a field of 500 yards.

A few days after the 9th Lancers lost to the Royal Horse Guard at Windsor, they were playing again, this time against the 1st Life Guards. It was very well attended by a large detachment of the “élite” of London society. “The Star” reported that, “The costumes of both parties were perfect and picturesque, the Lancers wearing red forage caps with gold bands, white flannel shirts, and red ties, and red and gold belts; the Life Guards being distinguished by blue caps and belts, with red silk shirts.” This time, the Lancers won.

Polo was “off to the races,” so to speak, and was soon being played throughout England. Universities and colleges began forming teams and clubs were being created across the country. The Hurlingham Club, which began as a gun and pigeon shooting club in 1867, published the first set of broadly acceptable rules in 1874. That same year, the International Gun and Polo Club began meeting near Brighton where their fancy-dress balls became famous. Polos popularity extended to numerous pieces of music, including the “Polo Lancers,” composed by the bandmaster of the Grenadier Guards.

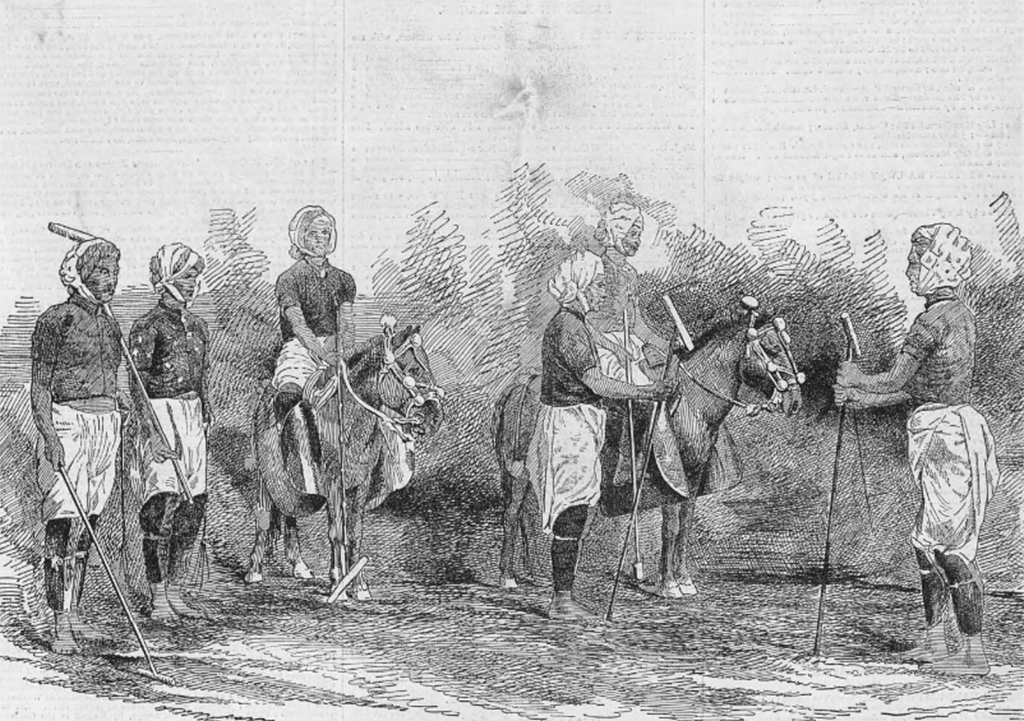

The Indian team at Calcutta for the Prince of Wales’ visit. The formed leather fenders to protect the rider’s legs can be seen.

Cycling back to the inspiration from India, when the Prince of Wales toured India, he was treated to a polo match between the Calcutta Polo Club and a local team on Jan. 1, 1876. It was reported to be the highlight of the prince’s visit. The Manipur team rode barefoot in stirrups. Placed under their saddles where a blanket would be, was a large leather skin formed to curve around the riders’ legs, forming a protective fender. It was reported to make a tremendous noise that would inspire the ponies to keep moving. Among the numerous gifts presented to the prince on his trip was a Manipur polo saddle.

Two years later on July 18, English polo reached another landmark, when the newly formed Ranelagh Club, hosting Hurlingham, staged the first nighttime match to be played under electric lights, followed by fireworks. Polo had clearly arrived. ML

This article first appeared in the July 2020 issue of Middleburg Life.