Then & There: When Halloween was Serious Business

By Richard Hooper

It is almost Halloween, and as with many things, there are numerous sources to its origin and evolution. Within the Christian tradition, Halloween is known as All Hallow’s Eve and observed on the last day of October. In that tradition, Nov. 1 is observed as All Hallows Day and Nov. 2 as All Souls Day.

The Christian holidays correspond to the Celtic celebration of Samhain and its pagan roots that originated in Ireland and Scotland. Essentially, Samhain translates as the “end of summer.” Calan Gaeaf (the “beginning of winter”) was celebrated in Wales and, with variations to the name, in Cornwall, and Brittany in France.

Halloween has spawned many traditions: from apple bobbing and roasting nuts to sessions focusing on divining the future and setting a place at the table for the departed as they returned home for these special days. Early on, it was a time when the wall between the other world and the earthly world was more easily passed through. Bonfires were lit to ward off the darkness of winter in some localities and, in others, to prevent the souls of the dead from falling to earth and to hold the devil at bay.

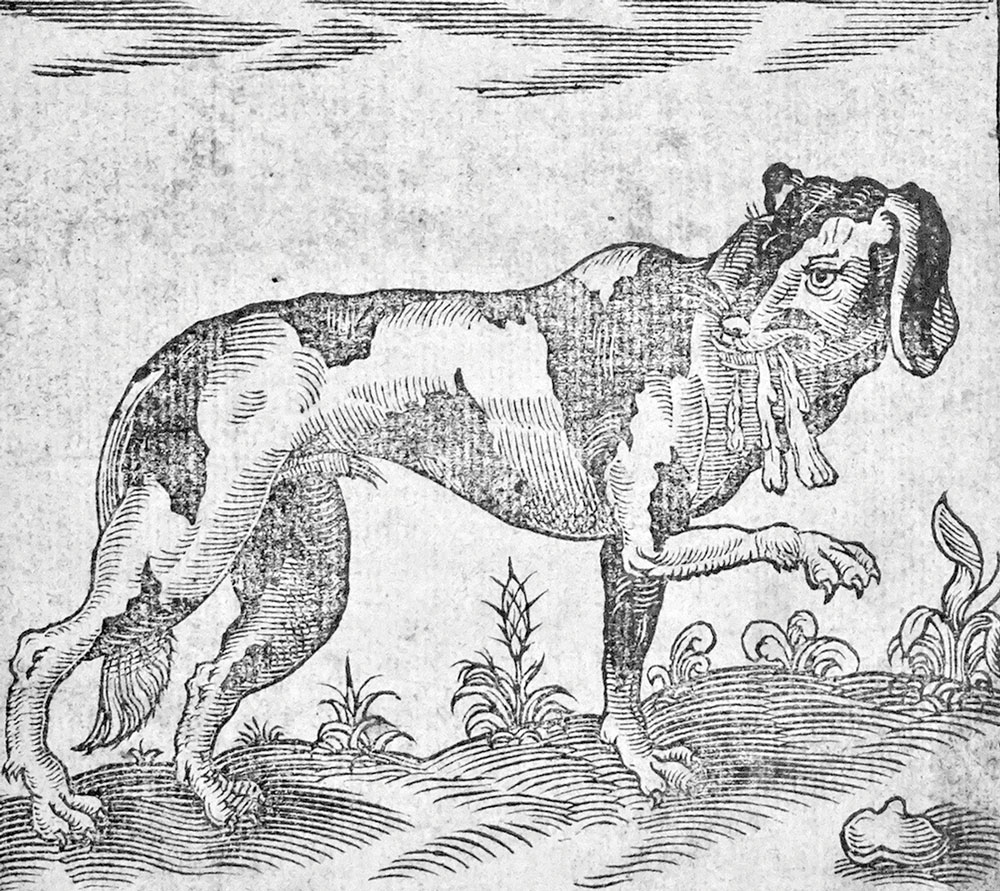

Scary visages were carved into turnips that were used as lanterns to ward off evil spirits. As early as the 1500s in Ireland and other areas, people would go door-to-door in costumes representing the spirits of the dead. They would recite verses in exchange for food. In Wales, the costumes could represent grotesque beasts. Many of these traditions have continued or morphed into those of our own. The turnip lantern has become the carved pumpkin, and costumed children canvas neighborhoods seeking treats.

Costumes have evolved as well. Today’s costume can be a sheet with cut out eye-holes, a black skeleton jumpsuit, a mask of a well-known personality (worn in either veneration or ridicule) or a portrayal of a Gothic inspired character such as Frankenstein, a vampire or a werewolf.

Like Halloween, the werewolf has many sources that have led to its creation. In doing research for a new book project, I was struck by descriptions of the sufferings of people bitten by rabid animals. These were scenes that could be easily adapted into novels or movies about werewolves. These adaptations would be fictional, but throughout a long portion of history, witches, spirits and demons were serious entities to be dealt with by mere mortals. Men thought to be werewolves were put to death.

One particularly graphic account of a man suffering from hydrophobia was published in 1683 by the English physician, Martin Lister, who was brought in to attend to James Corton, who had been bitten by a dog but shown no symptoms for over a month. When liquids were brought to the patient to drink, “he vehemently started, and his stomach swelled and rose, after a strange manner; and I could then find his pulse trembling and disturbed.”

Again Lister urged him to drink and edged the beaker toward the patient’s lips, “he more affrighted drew back his head, and sighed, and eyed it with a most ghastly look, not without shrieking and noise.” Lister noted that the Corton, “could take solid things in a spoon, but yet not without much trembling, fear, and caution, and an earnest request that nobody would suddenly offer them to him, but give them into his hand gently; and then he would by degrees steal his hand softly towards his mouth, and of a sudden chop the spoon in and swallow what was in it like a dog,”

Lister had Corton lie across the bed on his stomach and his head toward a bowl of beer placed on the floor and that, “In this posture of a dog… he endeavored with great earnestness to put his head down to it, but could not; his stomach rose as often as he opened his lips; at length he put out his tongue and made towards it as though he would lap; but as his tongue touched the surface of the beer, he started back affrighted.”

Corton was intrigued when the beer had been presented to him and “he followed it by the smell with delight, snuffing with his nostrils.” Corton decided he needed a stronger drink, and when that was brought to him he tried again, “but after much striving, and exerting his tongue a thousand times, he could not drink of it; and lapping with great affrights, as oft his tongue touched it he started back with his head, bringing it down again gently to the bowl a hundred times, but all in vain.”

These were only some of Lister’s descriptions of Corton’s pain and suffering and it saddens today, even these many centuries later, to read of his condition. Before Corton’s death, he had one last convulsive fit when, “he bit and snarled, and catched at every body, and foamed at the mouth.”

Here is the emblematic violent behavior and canine attributes associated with werewolves. The growing of hair and fur stems from another source, hypertrichosis, sometimes called the “werewolf syndrome.” It is a rare condition of excessive hair growth that can occur over the entire body or to a restricted area, such as the face – where it covers a much larger area than a normal beard. While a rare condition, its existence has been recorded for centuries.

There is one more source, known as lycanthropy, where people believe that they have shape-shifted into the form of a wolf, or some other dangerous animal that is prevalent in their environment. The condition takes its name from fears of werewolves (and of course real wolves) that existed in prehistoric times. In a central area of ancient Greece that was plagued by wolves, the inhabitants performed an annual ritual at Mount Lycaeus (lykos being the Greek word for wolf) in which anyone partaking of a certain food mixed with human parts would be turned into a wolf. This worked its way into Greek mythology in the story of Lycaon, the King of Arcadia, who tried to trick, or treat, Zeus into eating human flesh. Zeus, who knew what Lycoan was up to turned him into a wolf.

Also originating with the ancient Greeks was the idea that the phases of the moon could affect the brain, such as it did the tides. And we have the idea that the full moon can create the raging lunatic and is necessary for the metamorphosis of man into werewolf. In numerous, but by no means all, accounts, it is recorded that the onset of hydrophobia occurred at the time of the full moon.

So this Halloween, while we may still harbor some concerns about vampires and Frankenstein monsters, we are safe from werewolves. The moon will not be full. ML

This article first appeared in the October 2019 issue of Middleburg Life.